An amazing discovery from the good folks at the Internet Archive. Visit the Off Bunker Hill list, where LA historians and former Bunker Hill residents have been identifying structures and dating vehicles. One person even thinks they’ve spotted their father leaning on a lampost!

Tag: 400 Block

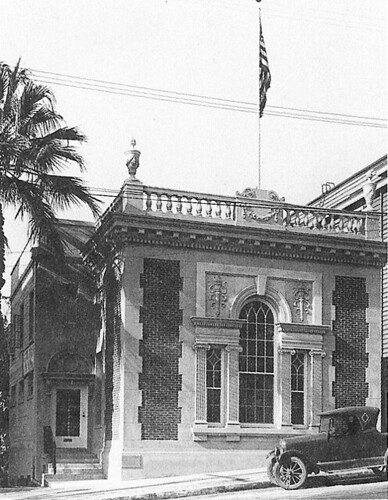

Architects’ Building

It’s not an Edwardian octoplex full of grime and grifters. It‘s not even on Bunker Hill. But we‘re going to tell the tale of the Architects‘ Building, and if not to you, faithful OBHer, then to whom?

All and sundry weep for the Richfield. It‘s not altogether true that everyone turned a blind eye during its”68-9 demo. Even the Government knew enough to come on out with its Instamatic and take lots of snaps.

The November 1968 Times article “Black and Gold Landmark: End Arrives for LA‘s Richfield Building” discusses those architecture students who believed the structure a remarkable example of “Jazz Moderne” worthy of preservation.

And the only mention of the Architects‘ Building at 816 West Fifth (which by 1968 had been renamed the Douglas Oil building) and which shared the block with the Richfield was as such:

”¦and that was the end of that. According to Cleveland Wrecking‘s general manager, the million-dollar site clearance project, of the block bordered by Fifth, Flower, Sixth, and Figueroa, was the largest ever undertaken in the West.

What is this Architects‘ Building of which we speak? Who architected this interbellum edifice?

Downtown is very nearly defined by Parkinson, and you can‘t mention LA without Morgan, Walls & Clements (Stiles sitting in the softest spot of this writer‘s heart), and if I mention Walker and Eisen, you‘ll say Yaaay! and I‘ll agree, and we‘ll high-five, and then get cut off and kicked out of wherever we are. It sure is swell to take those Conservancy tours and see all these places, but when the Conservancy cats go back to their digs, they return to a Dodd and Richards.

And you say, who?

William J. Dodd, student of Jenney and Beman is one of the great Midwestern architects. He came to California and is credited–though scholars still dispute to what extent–with a portion of Julia Morgan‘s 1914-15 Examiner Building. This he did with his partner at the time J. Martyn Haenke. In 1916 he partners with engineer William Richards. They produced so many an important Los Angeles structure that I will at some point in the near future add their full history as a comment appendage to this text, to keep from having too many appetizers before our twelve-story entrée.

We’re talking about the southeast corner of Fifth and Figueroa, not to be confused with our friend on the kitty-corner to the northwest, the Monarch Hotel.

The first rumblings about the southeast corner of Fifth and Figueroa come in February 1926, when mention is made of preliminary plans and lease negotionations for a million-dollar skyscraper to house LA‘s building trade. Sponsoring the project are Morgan, Walls and Clements, Dodd and Richards, Reginald D. Johnson, Webber, Staunton and Spaulgin, Carlton Monroe Winslow, Elmer Gray and McNeal Swasey.

The big announcement is made in February 1927 about the $650,000 height-limit to be built on the southeast corner of the Fifth and Figueroa. To be known as the Architect‘s Building, after New York and Chicago, it would be the third of its nature in America: a whole structure exclusively devoted to the various branches of the construction industries. It is to be of a “modified Italian” architectural treatment according to the associated architects drawing up the specifications: Roland E. Coate, Dodd and Richards, Reginald D. Johnson, McNeal Swasey, Carleton Monroe Winslow, and Witmer and Watson.

Twelve stories high, with a site of 60 by 156 feet, it is to be of steel reinforced concrete, 143 offices, its exterior finished in plaster with cast-stone trimmings. Its seven upper floors of the building are to be leased to prominent architects, its first floor and mezzanine to be occupied by the Metropolitan Exhibit of Building Materials–a massive exhibit of every branch of the building industry, renamed the Architects‘ Building Materials Exhibit.

By November of 1927, the building was nearing completion. Preston S. Wright, president of Wright-Aiken, owners of the AB, ran down some of the tenants: Rapid Blueprint Company; D. C. Writhg, insurance; E. E. Holmes, insurance; William Simpson Construction Company, builders; Brian D. Seaver, attorney; and architects D & R, Coate, Johnson, Winslow, and William Lee Wollett.

816 opens in January, 1928. It came in at $662,000.

The depression would not be good to the Architects‘. It was foreclosed on its $360,000 outstanding bonds in February 1933. It was put under federal receivership and forced into a court-ordered sale, which didn‘t occur until May of 1938, when an F. V. Fallgren and associate could pony up the 300k to a trustee representing the bondholder‘s committee.

The Architects‘ Building survives just fine through the 40s and 50s.

One bit of drama: Evans Erskine, 34, a jobless Air Corps vet, figured that 1955 would be Year Last. He climbed to the ninth-floor fire escape of the Architects‘ Building and hoisted himself over the railing. Richard McGowan, a controller for Dames & Moore Civil Engineers, ran down the hall and and grabbed the hands of the nattily dressed, ledge-teetering Erskine poised 100 feet above Fifth Street. Here, McGowan reenacts his daring hand-grabbing:

In 1959 it is purchased by Douglas Oil, a southern California independent who run three refineries and 300-some gas stations in the Southland. It remains the Douglas Oil building despite Douglas‘ purchase by Continental Oil (AKA Conoco) in 1961.

It‘s the 1960s when the folk in 816, heck, the building itself, could hear the dirge of doom wafting on the wind. Listen, it‘s coming from over by the Richfield building.

Richfield, another oil company, who owned that big ol‘ black and gold tower to the south, had merged with east coasters Atlantic Refining in 1966. Richfield had already begun buying up the block for piecemeal parking, and as Atlantic-Richfield Co. they purchased the whole kit. And kaboodle. That called for the end of the Architects‘, as ARCO intended to build not one but two Miesian towers (though their New York twin-tower counterparts broke ground four years earlier, there appears to be an aesthetic epoch between AC Martin’s work and Yamasaki’s tube-frame twins of lower Manhattan, whose postmodern sensibility stems from a neo-Gothic use of aluminum).

1967, and all‘s well:

1969, during the demolition. The Architects‘ Building, now one-fifth off! The Richfield, now with two-thirds less Richfield!

1970, towers going in.

Left to right, the Tishman Building (Victor Gruen, 1960, though you know it like this), Glore Forgan Staats, the Gates Hotel (now a fine Brooks Bros), St. Paul‘s Cathedral (razed), the Hilton (note how it changed from the Statler to the Hilton between 67 and 69), the Jonathan Club , the Carlton Hotel (razed), Caldwell Banker.

Below, today. Note the wee bit of the Jonathan peeking out.

The ARCO Towers still stand in all their glory. For now.

Another shot of the demolition. The Sunkist, Engstrum and Edison line Fifth. The Telephone Tower on Grand. In the distance, left, Bunker Hill Towers going up.

A mid-60s aerial. Central Library bottom right. The Sunkist at Fifth and Hope. Halfway up Hope behind the Sunkist, the tiny Sons of the Revolution and the Santa Barbara. The big apartment building at the southwest corner of Fourth and Hope was the Barbara Worth.

Of course we’re not getting away without the requisite model and Sanborn additions:

Note how Fourth Street ends at Flower. Compare to the 60s aerials which indicate the magnitude of the 1954 Fourth Street Cut.

Just to clear up one bit of confusion. Despite early mention that this building was to be of the combined effort of Roland E. Coate, Dodd and Richards, Reginald D. Johnson, McNeal Swasey, Carlton Monroe Winslow, and Witmer and Watson”¦it‘s a Dodd and Richards. Even Adrian Wilson, who in April 1967 wisecracked “I hope our new location won‘t be so temporary” in an article about his having to move out of the AB after thirty-nine years, remarks that Dodd and Richards designed the building–and he should know, the plans for 816 are inscribed with his own initials, as he was their draftsman before he hung out his own shingle when the building opened in 1928.

Clockwise from the south: Sixth, Figueroa, Fifth, Flower:

That then is the tale of the Architects‘ Building at 816 West Fifth. Remember the diaspora the next time you‘re in the neighborhood.

Images courtesy Los Angeles Public Library photo archive, University of Southern California, and Arnold Hylen and William Reagh Collections, California History Section, California State Library

Icarus and the Auto

People land on cars. They just do. It‘s how Daredevil and Crank end; it‘s how Lethal Weapon begins. Pauly lands on a car in Darkman; Conan O‘Brien lands on a car in South Park: Bigger, Longer and Uncut. And then there‘s George Costanza‘s suit against the hospital whose mental patient landed on his automobile. Clinicians call it the Evelyn McHale Syndrome, or at least I do.

In December of 1941, Mrs. Charlotte Neill, 70, called the gas company to turn on service at 2536 Reservoir Street. The Gas Co. sent out Perry C. Butler, 48, who attacked her, causing shock and other injuries necessitating her hospitalization.

Arrested the 26th, arraigned the 29th and free on bail, Butler was five days later, for some reason, atop the Subway Terminal Building. But not for long. It‘s unclear as to whether he fell or jumped the ten floors and crashed to the top of a car on the roof of Savoy Garage.

Assuming Butler jumped, it makes one consider that the auto is the modern equivalent of the sword, which Saul so famously fell upon after battling the Philistines. But consider: Detective Lieutenant B. G. Anderson was lead investigator in the apparent suicide attempt. Because Anderson was also, by coincidence, arresting officer in Charlotte Neill‘s attack case, it makes one wonder if this particular car-landing didn‘t have an element of the Ness/Nitti to it.

Above, the Subway Termial Bldg at right, adjoining the low-slung Savoy Garage onto which Butler made his car-smashing plunge.

Sons of the Revolution–437 South Hope

This episode, we‘ll be less concerned with the reprobate, the raconteur, the religious zealot, or good folk who fell into bad judgment; instead let‘s meditate on those went above and beyond the call of duty to make this country what it is, and in the most literal sense, made this country. The Bunker Hill of Israel Putnam and his bayoneted muzzleloader, not the Bunker Hill of Albert Duarte and his oversized bow. Perhaps because of the revolutionary association to the Bunker Hill appellation, and because Bunker Hill in the pre-Crash era still held some credibility and panache, it was to where the Sons of the Revolution came to have their library, 437 South Hope Street.

This episode, we‘ll be less concerned with the reprobate, the raconteur, the religious zealot, or good folk who fell into bad judgment; instead let‘s meditate on those went above and beyond the call of duty to make this country what it is, and in the most literal sense, made this country. The Bunker Hill of Israel Putnam and his bayoneted muzzleloader, not the Bunker Hill of Albert Duarte and his oversized bow. Perhaps because of the revolutionary association to the Bunker Hill appellation, and because Bunker Hill in the pre-Crash era still held some credibility and panache, it was to where the Sons of the Revolution came to have their library, 437 South Hope Street.

The Sons of the Revolution–open to those with a lineal descent from those who fought for the Patriot cause (not as hard to get into as the Society of Cincinnati, but harder to get into than the Sons of the American Revolution, which wasn‘t founded til thirteen years after the Sons of the Revolution, for reasons I won‘t get into here)–seeks to forever keep alive the first men to fight for our treasured traditions. And perhaps because YOU had some great great somebody at Cowan‘s Ford, they keep a genealogical library so that you may do the necessary research into possible membership. Today, their 110-year-old collection has 30,000+ volumes kept open to the public, free of charge, in Glendale; but the road there has been bumpy, save for forty years of comparative calm on the Hill.

The Sons of the Revolution of California was founded in 1893, and by the turn of the century had some 5,000 volumes regarding the Revolution and Colonial America, especially in relation to the West. Its first establishment was in the offices of the Society‘s first President, Col. Holdridge Ozro Collins.  Collins was a Los Angeles lawyer (who, besides organizing the California Sons of the Revolution and Society of Colonial Wars, was Mayflower Society, Colonial Governors, Society of the War of 1812, Knights Templar, and Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company of Massachusetts) whose officers were in the Bryson Block.

Collins was a Los Angeles lawyer (who, besides organizing the California Sons of the Revolution and Society of Colonial Wars, was Mayflower Society, Colonial Governors, Society of the War of 1812, Knights Templar, and Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company of Massachusetts) whose officers were in the Bryson Block.

Bonebrake-Bryson Block (Joseph Cather Newsom, 1888), NW corner of Second and Spring, shown here before and after its remodel. It was further remodeled into an open pit, as its corner site is now where the 1948 Times Mirror Building stands.

The Society stayed in the Bryson Block from May of 1893 until June of 1894, when Collins moved his offices, and the library, into the brand-spanking-new Stimson Block (Carroll H. Brown, 1893), NE corner of Spring and Third.

The Stimson Block was the first six-story building in Los Angeles, the first steel frame building in Los Angeles, and the last major example of commercial Richardsonian Romanesque in Los Angeles when it was unceremoniously demolished for a parking lot in July of 1963. (We do have a good extant Victorian Richardsonian house”¦and it‘s also Stimson‘s.)

In any event, Collins and the library stayed at Stimson Block until it was decided that it was time for Col. Collins to get his room back, and for the library to have a place of its own.

So when the Henne Building, 122 West Third, a five-story French Renaissance office building also designed by Carrol H. Brown opened in the Spring of 1897, the Society took out an office. The Henne site, west side of Third between Main and Spring, is now buried under the Ronald Reagan State Building (Welton Becket and Associates, 1990).

So when the Henne Building, 122 West Third, a five-story French Renaissance office building also designed by Carrol H. Brown opened in the Spring of 1897, the Society took out an office. The Henne site, west side of Third between Main and Spring, is now buried under the Ronald Reagan State Building (Welton Becket and Associates, 1990).

But the Society kept growing, and a decade later–January, 1908–they were moving boxes into the San Fernando Building (John F. Blee, 1906), SE corner Fourth and Main.

They started knocking out walls on the sixth floor until additional stories were added in 1912 and the Society moved into quarters specifically designed for the library. By 1914, they outgrew even that and had to take on an additional room. Making matters worse (good for the library, bad for space concerns) was that Orra Eugene Monette, aka Mr. Bank of America, Society President, (Mayflower, Colonial Wars, Huguenot Society, ad infinitum) gave a large collection to the library.

Again showing their preference for new buildings, the Society turned their eye to the new Citizen‘s National Bank Building (Parkinson & Bergstorm, 1914) at the NE corner of Fifth and Spring; the building is still there, but has mysteriously been stripped of its architectural embellishments.

And there they stayed until Nathan Wilson Stowell donated to the Society a plot of land on Bunker Hill.

As a master of pipe and irrigation, Stowell became one of the great Southland water gods; in 1889 he built the Stowell Building, AKA the Germain Bldng, at 224 S. Spring (first five-story building in Los Angeles with an electric elevator) and fans of Spring Street surely know the 1913 Stowell Hotel; he built the Mayan Theater and financed the 1924 Second Street tunnel.

As a master of pipe and irrigation, Stowell became one of the great Southland water gods; in 1889 he built the Stowell Building, AKA the Germain Bldng, at 224 S. Spring (first five-story building in Los Angeles with an electric elevator) and fans of Spring Street surely know the 1913 Stowell Hotel; he built the Mayan Theater and financed the 1924 Second Street tunnel.

When Stowell died in 1943, he was the last of the 20 charter members of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce. (And although his forebear who came to Massachusettes in 1620 was named Samuel, and the rest of his mishpucha are variously named Abraham, Isaac and Israel, Nathan maintains he is a Protestant.) Despite his importance to the history of Los Angeles, or perhaps because of it, some cultural terrorist elected not to restore his name to the Stowell, which was renamed the Earle in 1950 after its acquisition by the Milner chain, and redubbed the El Dorado in 1955.

So Stowell donates the land to the Society and made a point of submitting his own plans for the building, to cost $25,000. In October 1927, they held a ceremonial groundbreaking to turn the first shovelful of earth:

Left to right: Lansing Sayre; Rt. Rev. William Betrand Stevens, Bishop of Los Angeles; William Bowne Hunnewell (Gov., California Society of Colonial Wars. 1926-27); Philip E. P. Brine; Dr. Daniel L. Ransom; James D. Hurd; Dr. Edward M. Pallette, President; Wilson Milnor Dixon, Librarian (holding shovel); Charles B. Messenger; Orra Eugene Monnette (waving hat); Charles F. Bouldin; Dr. Egerton Crispin; unknown; Cassius Milton Jay, Secretary; Col. Harcourt Hervey, Marshal; Edward Bouton, Jr.; Dr. James D. Eaton.

Left to right: Charles F. Bouldin; William Bowne Hunnewell (Gov., Colonial Wars); Edward M. Pallette, President, shaking the hand of Willis Milnor Dixon, Librarian; Lansing Sayre; John Emerson Marble; Orra Eugene Monnette (holding hat); Dr. Egerton Crispin; Cassius Milton Jay; Burnham Robert Creer (partially hidden); Edward Bouton, Jr.; unknown; Dr. James Demarest Eaton; and Dr. Daniel L. Ransom.

Left to right: Mrs. Frank Pettingell; Hon. Benjamin Bledsoe (U.S. District Judge; future Society President and General President Sons of the Revolution); Dr. Egerton Crispin; Bishop William Bertrand Stevens and Dr. Edward Marshall Pallette.

Above, on November 26, 1927, Dr. Pallete officiated at and Bishop Stevens conducted the services at the laying of the cornerstone. Within the cornerstone were deposited historic documents from the Sons and Society of Colonial Wars, along with 7th century Arabic manuscripts; a Spanish silver seal from the time of Ferdinand and Isabella; a California pioneer gold dollar of 1854, and a pass through the Continental lines issued in 1871 by the Supreme Executive Council of the Pennsylvania Colony.

The library opened to the public February 1, 1928.

They burned the mortgage in 1935:

Left to right: unknown; Lansing Sayre; unknown; Nathan Wilson Stowell; Willis Milnor Dixon; Orra Monnette; Hon. Benjamin Bledsoe (General Registrar, General Vice President, 1934, General President, SR, 1937); W. W. Beckett; James Black Gist; E. Palmer Tucker, President (sitting); Rt. Rev. William Betrand Stevens (Episcopal Bishop of Los Angeles, General Chaplain, General Society of the SR, 1940-1947); Dr. Edward M. Pallette; Egerton Crispin; unknown; and Cassius Milton Jay (Treasurer).

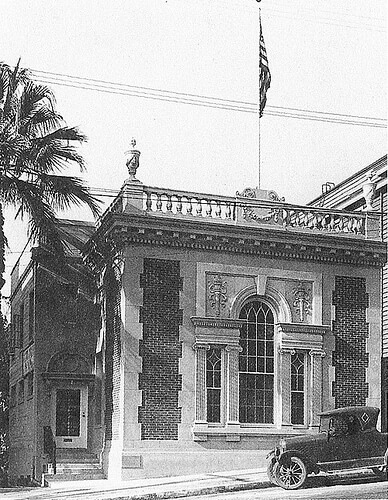

Now then, of the building.

Let‘s talk Stowell‘s style. In the last ten months of OBH you‘ve seen a lot of structures, but nothing quite like this handsome dentil‘d and bequoin‘d Georgian. The Federal-style flat roof behind the balustrade, and that Palladian window”¦what does that remind you of? Come on”¦

Of course”¦what could be more appropriate than appropriating from Independence Hall?

Inside, what more could one ask for?

The secretaire with broken pediment, the Ionic capitals, the Doric pilasters, the plaster medallion, the comforting keystone? One can gain an almost perfect serenity from gazing into this image (imagining the hypnotic tick-tock of an Elias Ingraham on the mantel…kept me in ataraxia all these feverish months, allowing me to postpone this post to President‘s Day).

Another corner of quietude and sobriety:

The library opened its doors to other patriotic and hereditary societies, e.g. the Society of Colonial Wars, Order of Founders and Patriots, and the Mayflower Society; of course the DAR hosted more than a few luncheon n‘ lectures.

While the library naturally abjured the wild Bunker bacchanal, perhaps we should make mention that it did have some interesting neighbors (okay, so this post doesn‘t get away totally scot-free when it comes to tales of queer criminality).

Though the Touraine and Santa Barbara aren‘t so bad that one can conjecture Stowell‘s gift had at its core his desire to divest himself of this property, it was sandwiched between the two.

Though the Touraine and Santa Barbara aren‘t so bad that one can conjecture Stowell‘s gift had at its core his desire to divest himself of this property, it was sandwiched between the two.

437, between the Touraine and the Santa Barbara, before the 1927-8 Society building (Sanborn Map, 1906) and after (Sanborn, 1950):

Tales of the Tourained.

The Santa Barbara, to the immediate north at 433, is announced in August, 1903.

The Santa Barbara, to the immediate north at 433, is announced in August, 1903.

Girls were dazzled, and the white way was brightened, with the arrival of dapper nobleman Count Jean de Marquette. His dash and vivacity made for a meteoric café career, which has come crashing down in Justice Brown‘s court, December 10, 1915.

Girls were dazzled, and the white way was brightened, with the arrival of dapper nobleman Count Jean de Marquette. His dash and vivacity made for a meteoric café career, which has come crashing down in Justice Brown‘s court, December 10, 1915.

Mrs. Helen Roberts, Miss Eva Knoll, and Mrs. M. Brader, of the Santa Barbara Apartments, were three of the ladies who fell under his sway. They probably found him less dashing as they stood in court and identified various articles of jewelry, looted from their rooms in the Santa Barbara, found in de Marquette‘s possession.

He also made the rounds as none other than Donald Crisp, and supported himself by writing ficticious checks as the actor/director.

Turns out that he‘s just Leonell Gianini, a repeated youthful offender who‘d been sent to Whittier for burglary. His folks are ranch owners with a farm out in Ocean Park Heights (renamed Mar Vista in 1924). Nevertheless, in court, he claimed the jewelry as heirlooms “from his ancient and honorable family” in France. He got five years at Folsom.

Herman Pfeiffer, a recent emigrant from Switzerland, was arrested in his apartment at the Santa Barbara, March 16, 1928, with mysterious tubes of green liquid and typewritten notes that read “I am a chemist and desperate. Hand over the money or there will be a tragedy.”

Herman Pfeiffer, a recent emigrant from Switzerland, was arrested in his apartment at the Santa Barbara, March 16, 1928, with mysterious tubes of green liquid and typewritten notes that read “I am a chemist and desperate. Hand over the money or there will be a tragedy.”

At his trial, Pfeiffer denied contemplating a bank robbery. “I am a somnabulist,” he explained. “On the morning in particular, I walked in my sleep and went over to the table to write this note, which was found by the detectives when they called several hours later. It was all a dream. I dreamed that I had held up a bank.” Deputy City Prosecutor Ford Q. Jack, reminding the court that in several recent hold-ups the same method had been employed, asked that to curb the dream alibi in prospective bank robbers, Pfeiffer be given the maximum sentence. Pfeiffer was then sentenced to 180 days in the City Jail to think up new uses for chemistry.

Of course, deep within the library‘s quietude, one couldn‘t hear the bulldozers rumbling. Surely through the 50s they knew which way the wind blew, and it blew some silent but foul CRA halitosis through the cracks in the early 60s. By 1964 the Society was given notice, and eventually some blood money for the building and expenses incurred for moving and storage. In November 1968 the Society had moved out the last of their collection; shortly thereafter the bulldozers were deafening. The latticed windows and oak flooring and everything Independence Hall went crack and crumble.

Today, the Citigroup Tower (AC Martin Partners, 1979) sits atop the Hope Street site.

The library took everything and moved into the Granada Shoppes and Studios, where they remained until 1971. Unlike anything on Bunker Hill, the Lafayette Park area was left in blithe poverty long enough to allow this building to survive and become an HCM (read about #238 on BOL in a few weeks) and eventually National Register.

From there they hunted around and these Colonial folk found another Colonial building”¦though again, Spanish Colonial. Built as the Glendale Chamber of Commerce Building in 1929, 600 South Central Avenue–all 4,300 square feet of it–proved the perfect space, especially after the Society filled it with Windsor chairs, gas lamps and (American) Colonial flags.

Even if your lineage is more McCorkel than Mayflower, more B&O of Locust Point than Battle of Eutaw Springs, still, go to the library to check out their painting of Fremont painted from life. Too cool. It‘s small library nirvana for those of us with a library fetish.

Very special thanks to President Emeritus Richard Breithaupt for his kind permission to use these images and this information. The vast majority of this post is a reworking of this page from the Library‘s website. (A few of the small images are California State Library; the later view of the Stimson is an Arnold Hylen.)

Truck Amok

When it rains, it pours. Which is probably a good thing, since rain will put out all that pesky fire.

When it rains, it pours. Which is probably a good thing, since rain will put out all that pesky fire.

Corner of Fourth and Olive, August 29, 1962.

Van R. Alexanian, 23, was loading a barrel of rubbish into the scoop on the front of his trash-truck when the parking brake gave way. The truck ran into an electrical pole, and the live wire caught the truck debris on fire. The pole then fell onto a Mrs. Helen Stairs, 50.

The flaming truck went on to take out a traffic signal and a lamp post before crashing into a garage. This much was fortunate; the garage attendant was equipped with a fire extinguisher.

Officer L. S. Rasic commented that had the truck continued through the intersection, it would have crashed into eight cars waiting for the signal to change.

The question remains as to what garage the garbage truck plowed into, as there were in fact three at Olive and Fourth: the 1923 Mutual Garage at the NE corner, the 1919 Hotel Clark/Center Garage at the SE corner, and the 1923 Savoy Garage at the SW corner. Here’s a picture of all three, 1966:

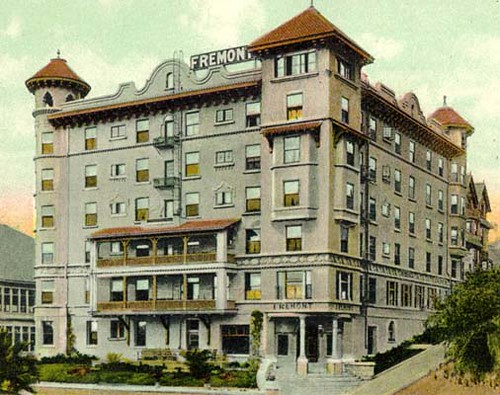

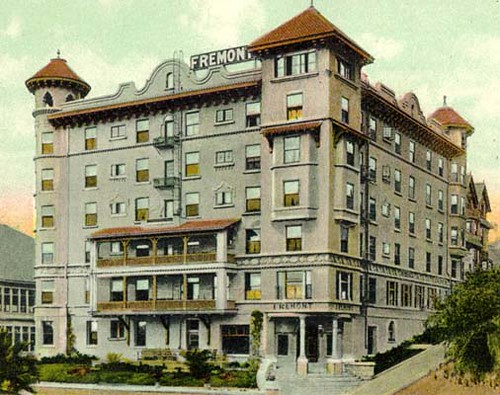

Remarkably, the Savoy still stands. The 600-car Mutual at left in the image above is now the foundation for Cal Plaza Two. The Hotel Clark Garage, center (along with that tall white building, ironically named the Black Building) is still an empty lot, site of what was to be Cal Plaza Three. (The parking lot at foreground right was the former site of the Fremont.)

Remarkably, the Savoy still stands. The 600-car Mutual at left in the image above is now the foundation for Cal Plaza Two. The Hotel Clark Garage, center (along with that tall white building, ironically named the Black Building) is still an empty lot, site of what was to be Cal Plaza Three. (The parking lot at foreground right was the former site of the Fremont.)

Should you wish to learn more about garages, please do so here.

Garage pic, William Reagh, Los Angeles Public Library

The Auditorium/San Carlos Hotel – NW Corner of Fifth and Olive

Dodge City. Tombstone. The OK Corral. Wyatt Earp will also be remembered as a guy who ran a piece of two-bit flimflam on Bunco Hill. And got popped for it–but then, this was no 1880s gambling saloon. This was the grandest new hotel in Taft-era Los Angeles. Perhaps Earp was a little out of his element.

After the turn of the century, Earp was based out of Los Angeles, trying his hand at the kind of gambling grown-ups do–oil exploration, mining ventures, real estate–with considerable less success than he‘d had at the card table. Occasionally he‘d work with LAPD on outside-jurisdiction work, like chasing fugitives into Mexico, but inveterate gambler Earp‘s core motivation remained gambling. This would on occasion put lawman Earp on the wrong side of the straight and narrow–e.g., his refereeing of the Fitzsimmons-Sharkey boxing match of ‘96, generally regarded to be fixed. And when Earp and his con-rades would set up their fleece outfit, where else would they go but that anchor of Bunker Hill, the brand-new Auditorium Hotel?

The Auditorium had been open a scant six months when on July 21, 1911, a J. Y. Peterson sat down for game of faro with three sharpers from San Francisco–W. W. Stap, Waller Scott, and E. Dunn. But all would not go as planned.

Seems that Peterson–a real estate agent with an office at 407 Stimson Building–got hinkey at the trio‘s far-out tale that they were sore at their SF syndicate, and wanted to stiff their own backers by rigging the game to let Peterson win big. Peterson would thus play the rigged game–pinpricked odd cards, the dealer placing a finger on the table when an even card was to show–in front of others, and make a hefty profit on the $2,500 ($54,985 USD2007) he‘d invest at the outset in chips. Realizing he had nothing to lose except his roll, he called in the coppers.

Stap, Scott, and card-dealer Dunn engaged club rooms 425-426 at the Auditorium, installed their faro bank outfit and all kindred paraphernalia, and were ready to get down to the business of swindling Peterson–who was further tipped off to that fishy smell in Denmark as there were no other players present–when Johnny Law busted in.

Down at the station-house, the W. W. Stap who inveigled Peterson into buy into a fixed bank game turned out to be none other than Wyatt Earp. Released from City Jail on $500 bond, Earp‘s explanation was that it was purely accidental that he should be there during the raid. The police, in their infinite wisdom, elected to bust into the room before any gambling actually begun, which sank the conspiracy to defraud charge; the courts couldn‘t make a vagrancy charge stick, either.

In the end, the City Prosecutor decided there wasn‘t enough evidence against Earp. Waller Scott pleaded guilty and demanded a jury trial, but the City Prosecutor “didn‘t have the time” to take it up and let the whole thing drop. Dunn, aka Harry Dean, pleaded guilty and was given a six month sentence, suspended, on condition that he leave the city. And so Wyatt Earp went on his six-shooterin‘ way: he hung around Hollywood and hit up William S. Hart to publicize his life. That never happened, ended up dying down on 17th Street, and was buried in a Jewish cemetery in 1929.

In the end, the City Prosecutor decided there wasn‘t enough evidence against Earp. Waller Scott pleaded guilty and demanded a jury trial, but the City Prosecutor “didn‘t have the time” to take it up and let the whole thing drop. Dunn, aka Harry Dean, pleaded guilty and was given a six month sentence, suspended, on condition that he leave the city. And so Wyatt Earp went on his six-shooterin‘ way: he hung around Hollywood and hit up William S. Hart to publicize his life. That never happened, ended up dying down on 17th Street, and was buried in a Jewish cemetery in 1929.

Finest New Hotel in Modern Christendom

“It will command a view of perennial green, unsurpassed in the heart of any great city!”

What was this this hotbed of vice, the Auditorium Hotel? Only the finest new hotel in Christendom, mister. (“It will command a view of perennial green, unsurpassed in the heart of any great city!”)

It all began with the northwest corner of Fifth and Olive, facing Central Park. (I know, the purist in you wants to object that we‘re not technically on Bunker Hill. Well, think of the Auditorium Hotel as our landmark edge to the south. The Jaffa Gate, if you will. Angels Flight is the Dung Gate and we‘ll call the Monarch Hotel Damascus Gate while we‘re at it. Naturally you‘re continuing to argue that the Edison Building makes a better Jaffa Gate than the Auditorium Hotel. Well, you would say that.)

Auditorium architect Otto Neher, with partner Chauncey Fitch Skilling, produced the New Auditorium Hotel, designed in what the papers for lack of a better term called the “Modern Classic” style. It was 60×162‘, faced with light-colored granite, the lobbies lavished in marble, mahogany and mosaic tile. The six floors of 150 rooms are paneled in birch.

A look up Olive–the three biggest buildings behind the Auditorium are the Trenton, the Fremont, and the Palace Hotel:

The Auditorium is leased by Bernard Frank Green and his mother, Mrs. Mary Sells Green; in 1919 M. Drake Perry takes over the lease and buys the hotel from R. D. Wade in 1921. He puts in a grill room and makes another $100,000 in improvements. But the shock of the Biltmore Hotel being built on the opposite corner apparently killed Perry, and Probate Court sold the Auditorium Hotel to George Roos.

(The Biltmore to the left; the 1924 Pacific Telephone and Telegraph Company Mutual Exchange is under construction. The Deaconess/Clara Barton Hospital between the Methodist church and the new telephone building doesn’t have many days left before conversion to an auto park.)

Roos (vintage clothing collectors out there certainly know the Roos Bros. label–George was one of those Rooses) eventually sells to Charles Harris, who held the lease and ran the hotel through the 20s.

It‘s an exciting time: everyone‘s abuzz about the sale of the California Club at Fifth and Hill to the Title Guarantee and Trust Company, and the forthcoming home of California Edison at Fifth and Grand. Harris refurnishes 100 rooms and renames the Auditorium the San Carlos in January 1929. Why? Because at that point he was spending most of his time in Phoenix, directing the opening of his mighty San Carlos there. Just as there were once matching Auditoria, there were now Sister San Carloses. Charles Harris in 1931 departs the Phoenix San Carlos for yet his third San Carlos, this one in Yuma. He eventually sells his Los Angeles SC in toto to G. G. Joyce, owner of the Hazlewood restaurant chain in Portland.

Here, in this mid-30s image, check out the San Carlos neon blade affixed to the wedding cake that is the former Auditorium:

The San Carlos then went through a streamlining much in the way the Auditorium did:

Now we all know that the redoubtable Claud Beelman was the architect-at-helm for the 1938 Philharmonic Auditorium redesign. This author is yet to discover when (and by whom) the San Carlos had its cleanlining:

The San Carlos made its way into the Modern Age, even acquiring a 1955 Armet and Davis Googies:

”¦so what became of our Jaffa Gate? Unlike most of Bunker Hill, it made it all the way through the mid-1980s. Here, you could hang at Googies and get a room at the Carlos to boot, ca. 1986; that‘s the Biltmore Tower going up in the background:

(But first, a map, so as to explicate the many addresses of the Auditorium/San Carlos.)

William Friedland was a cigar store clerk at one of the San Carlos‘s sidewalk shops. At least he was until February of 1939, when he got popped for making book therein. The establishment at 513 West Fifth had been raided many times for horserace betting, and in November 1940 Friedland had to go before the LA County Grand Jury to dish the dirt on a crooked horserace racket. He was grilled by none other than Jerry Gielsler, chairman of the Horse Racing Board, who disclosed the racing scandal. Swirled into the mix of our tobaccoshop/bookstore at the San Carlos were bribe-taking jockeys and horse owners, as well as local sharpies Benny Chapman, I. W. Kivel, aka Doc Kebo; Bernard Einstoss, alias Barney Mooney; and Saul “Sonny” Greenberg. Mooney and Kebo gave horse owner Irving Sangbusch (alias James J. Murphy) over $20,000 to bribe jockeys at Hollywood Park in 1939; by the end of 1940 the take was up to $180,000 on a single race.

William Friedland was a cigar store clerk at one of the San Carlos‘s sidewalk shops. At least he was until February of 1939, when he got popped for making book therein. The establishment at 513 West Fifth had been raided many times for horserace betting, and in November 1940 Friedland had to go before the LA County Grand Jury to dish the dirt on a crooked horserace racket. He was grilled by none other than Jerry Gielsler, chairman of the Horse Racing Board, who disclosed the racing scandal. Swirled into the mix of our tobaccoshop/bookstore at the San Carlos were bribe-taking jockeys and horse owners, as well as local sharpies Benny Chapman, I. W. Kivel, aka Doc Kebo; Bernard Einstoss, alias Barney Mooney; and Saul “Sonny” Greenberg. Mooney and Kebo gave horse owner Irving Sangbusch (alias James J. Murphy) over $20,000 to bribe jockeys at Hollywood Park in 1939; by the end of 1940 the take was up to $180,000 on a single race.

The jury heard testimony from a Clay Selby, manager of the Biltmore Garage, adjacent to the San Carlos. He asserted that the clicking of chips and rattle of dice could be heard from 511 West Fifth as early as 1925 (he remembered the date because that was about the time habitué-of-the-place Eddie Eagen was shot there in a holdup). Selby said that when 513 was in operation, he could hear loud-speakers announcing race results in the garage. When asked if it was loud enough for a policeman on the street to hear it: “Oh,” said Selby, “they all knew about it.”

The jury heard testimony from a Clay Selby, manager of the Biltmore Garage, adjacent to the San Carlos. He asserted that the clicking of chips and rattle of dice could be heard from 511 West Fifth as early as 1925 (he remembered the date because that was about the time habitué-of-the-place Eddie Eagen was shot there in a holdup). Selby said that when 513 was in operation, he could hear loud-speakers announcing race results in the garage. When asked if it was loud enough for a policeman on the street to hear it: “Oh,” said Selby, “they all knew about it.”

Things got even saucier when the horse trainer for Don Ameche and Chester “Lum” Lauck testified that he was approached by Bernard Mooney, and that Mooney wanted to fix Ameche‘s horses to lose races. Apparently Mooney enlisted his pal George Raft to have a friendly discussion with Ameche about the subject.

Of five defendants, only Bernard Mooney got nicked–for contributing the delinquency of minors. Minor jockeys, which legally should cancel itself out. Some $1,000 fines were assessed, but then, that‘s what these fellows spent on shoes in a month. Sure, the Black Socks made finageling baseball illegal, but what was so wrong with a little racetrack gratuity? Giesler went all nuts afterward and called for laws protecting boxing, football, wrestling…wrestling has, for example, been unhindered by money and scripting ever since. (One may read more about the scandal here.)

Let‘s stay on the subject of crime.

The Auditorium wasn‘t open six months before the help developed sticky fingers; in July 1911 bellboy Raymond Perry was nabbed in his hotel down on Grand between 5th and 6th, secreting stolen diamonds in his socks.

In 1919 Harry Royse decided to give up the life of a minister. The life of a Methodist clergyman–which he‘d led for ten years–lost its kick apparently, so he spent most of that ‘19 checking into hotels and burglarizing the stores therein, and sending ill-gotten gains to his new lady-friend up in San Francisco.

Royse was finally nabbed in the act with his fifteen-year-old nephew in tow, pilfering typewriters from the Auditorium‘s shop on the corner of Fifth and Olive. He was given one to fourteen at Q; the nephew went to juvenile hall, and the gal up north got no more pretty things.

The early morning of Dec 21, 1924 saw a the arrival of the “variety bandits.” Two men hit the Moon Drug Store at 3526 West Washington, forcing the soda clerk into the closet and making off with $200; they hit the Barnett Drug Store at 3723 South Vermont, where they locked up two women and emptied the register of $75 (during which time a customer entered; one of the bandits took off his cap and waited on the gent, selling him a magazine and pocketing the proceeds); they hit the Zenith Drug Store at 4929 Moneta, and made off with $60; and when they then hit Harry Spooner‘s drug store at 4493 Beverly Blvd, they got $30 and eight pints of whiskey. Maybe it was the whiskey. Maybe it was getting late. Maybe it was just time for their luck to change. Because things didn‘t go so well at the Auditorium Hotel.

Just before dawn, these two heavily armed gents muscled night clerk J. C. Evans into the back to open the safe. Though threatened with instant death, Evans claimed he didn‘t have the combination. As the two holdup men argued, Evans slipped away, and the bandits took right after him. Unfortunately for them, Evans had a good knowledge of the many doorways and halls of the lower floor, and got a good lead on them, long enough to turn, produce his own hand cannon, and open fire. The robbers, one of them apparently hit, had to make it out of the hotel in a mad dash and into their touring car and speed away into the first morning light, never to be heard from again.

August 14, 1927 was a red-letter day for crime in Los Angeles: armed men stole $2,000 in cash and jewelry, and a $1,500 car, from a auto dealership at 1355 South Main; two men were beaten and robbed by a gang of thugs at West Tenth St. near Georgia; two men in an automobile drove up alongside–a reverend, no less–Rev. Joseph Curran at Eightieth and Moneta, and robbed him without even getting out of their car.

Lastly, later that night, three gunmen showed up at the auto rental concern in the Auditorium Hotel to relieve manager D. C. Huff of $85 ($1,007 USD2007).

Reprobate gaming came back into fashion at the San Carlos in 1948”¦in the form of pinball. In March of 1948 nine men were arrested by the administrative vice squad for owning these marble contraptions, in flagrant violation of the City‘s antipinball ordinance. Asst. City Atty. Donald Redwine, however, doubts the arrests should have been made until someone comes up with a “clear-cut decision” on the legality of these newfangled games. Of course, pinball isn‘t exactly new, but if there‘s one thing 1947 gave us it‘s a pinball machine that (distributors claim) is a “game of science and skill.” That notwithstanding, one LaVerne Murphy is cooling his heels in the tank after vice squad raiders came down on his newfangled “flippered” machine in the San Carlos. (Even if they are just games of “science and skill,” you still can‘t own one without a permit.)

Let‘s move on from crime to death and despair!

In June of 1914, Mrs. H. G. Purcell, 50, a woman of wealth and taste, had come from Chicago to buy a lot and build a home in sunny Los Angeles. For two years she lived in the Auditorium Hotel, well-liked and highly sought after for social and cultural gatherings. And yet, her father having died of cancer, she believed, rightly or wrongly, that it was going to get her too, and drank a phial of carbolic acid in her room.

In June of 1914, Mrs. H. G. Purcell, 50, a woman of wealth and taste, had come from Chicago to buy a lot and build a home in sunny Los Angeles. For two years she lived in the Auditorium Hotel, well-liked and highly sought after for social and cultural gatherings. And yet, her father having died of cancer, she believed, rightly or wrongly, that it was going to get her too, and drank a phial of carbolic acid in her room.

February 1940, insurance man Jesse Edward Patty, 47, left his home at 1227 S. Plymouth Blvd. and checked into the San Carlos with murderous intent. Self-murderous. Several letters to his wife and friends later, he took poison.

L. D. Roberts, a 50-year-old lumber man, left his home at 7024 Mission Place in Huntington Park, July 1942, to check into the San Carlos. Roberts had problems, but brought with him a traditional problem-solver, the .32 automatic.

Joe Guiterrez, 45, lived at the San Carlos. He‘d been separated from his wife Rafaela Uriarte Guiterrez, 46, for two years. It was Sept. 3, 1941, and Joe had had enough of the San Carlos. He wanted to come home to their house at 1314 Sunset Blvd. He wanted a reconciliation. Always bring a gun to a reconciliation.

Joe Guiterrez, 45, lived at the San Carlos. He‘d been separated from his wife Rafaela Uriarte Guiterrez, 46, for two years. It was Sept. 3, 1941, and Joe had had enough of the San Carlos. He wanted to come home to their house at 1314 Sunset Blvd. He wanted a reconciliation. Always bring a gun to a reconciliation.

Rafaela‘s kids from a previous marriage were home–Rosie, 24, Lydia, 20, Mario, 16, and Carmen Uriarte, 14. Mom and “dad” hadn‘t been talking long when they heard the shot. Joe came out firing, the girls fled, Carmen took one through the knee and Lydia through the shoulder before Joe was tackled by Mario. Gutierrez shoved the gun into Mario‘s side and pulled the trigger, but the gun was empty. Mario kicked dad out the back door. Gutierrez reloaded his .25, and gave himself the same treatment he gave mom: one to the head.

And lest we forget “Miss Dale Erwin, 22, of Trenton, NJ” who checked into the San Carlos in August of 1946 and promptly leapt–or fell–from her window. As she landed in a second-floor courtyard, and there were plenty of taller hotels around, let‘s give her the benefit of the doubt.

Let‘s go back in time a bit and take a look at some of the folks who make the Auditorium so special.

Let‘s go back in time a bit and take a look at some of the folks who make the Auditorium so special.

One is Frederick Jordan, vice-president of the Entomological Society of England. The esteemed zoologist, whose soul is one with butterflies and moths and whose body is dedicated to the netting of terebrant hymenopterae–those that fly, of course–is a welcome additon to the Auditorium. But not as a guest. He‘s the night porter .

.

Seems his English doctor told him to get some sun, and not work too hard. Despite the lateness of the season–October, 1911–Jordan found Los Angeles choked with butterflies, especially the Spring Beauty, the Holly Blue, the Zebra Swallowtail, the Checkered Skipper, the Brown Argus, the Clifden Nonpareil, the Tortoiseshell, the Mother Shipton and the Duke of Burgundy Fritillary. That‘s great Jordan, now get back to work.

In the vein of any grand hotel (or, say, Grand Hotel), the Auditorium lobby was always full of great excitement, chance meetings, tearful partings, tearful reunions. Such was the case when Dr. D. A. Gildersleeve of Richmond was in town for a 1911 AMA conference to deliver the stirring paper “Hook-worm and What Has Been Done In the South Toward Its Eradication” when he was approached by none other than “Uncle Joe,” who had been residing on East Ninth St. for some years. Joe, it seems, had been a Gilderslave, childhood playmate of the good doctor‘s, had been Gildersleeve‘s servant in battle in all the campaigns of Lee, but had ended up “disenfranchised” after The War. Joe stayed with Gildersleeve for some years but eventually went up North; and now, some thirty-five years later, they were reunited by chance in the Auditorium. An hour of gossip followed between the two in the big chairs; when the doctor bade the older man farewell he was observed slipping him what appeared to be a roll of banknotes. In describing the meeting, the Times writer showed his considerable cultural acuity–or vacuity of cultural sensitivity–in any event, I‘m not going to transcribe it, but will here attach a clip of the encounter between what the Times describes as the “shambling darky” and what I imagine as a Harland Sanders/Maurice Bessinger-looking old ofay:

In the vein of any grand hotel (or, say, Grand Hotel), the Auditorium lobby was always full of great excitement, chance meetings, tearful partings, tearful reunions. Such was the case when Dr. D. A. Gildersleeve of Richmond was in town for a 1911 AMA conference to deliver the stirring paper “Hook-worm and What Has Been Done In the South Toward Its Eradication” when he was approached by none other than “Uncle Joe,” who had been residing on East Ninth St. for some years. Joe, it seems, had been a Gilderslave, childhood playmate of the good doctor‘s, had been Gildersleeve‘s servant in battle in all the campaigns of Lee, but had ended up “disenfranchised” after The War. Joe stayed with Gildersleeve for some years but eventually went up North; and now, some thirty-five years later, they were reunited by chance in the Auditorium. An hour of gossip followed between the two in the big chairs; when the doctor bade the older man farewell he was observed slipping him what appeared to be a roll of banknotes. In describing the meeting, the Times writer showed his considerable cultural acuity–or vacuity of cultural sensitivity–in any event, I‘m not going to transcribe it, but will here attach a clip of the encounter between what the Times describes as the “shambling darky” and what I imagine as a Harland Sanders/Maurice Bessinger-looking old ofay:

Yep, that‘s what it says.

Not all sightings at the Auditorium are happy ones. Leo Julofsky was a messenger for E. D. Levinson & Co., 52 Broadway, New York. He was walking down the street one day–September 19, 1919–with another messenger and $330,000 in Liberty bonds. On their way to Mabon & Co., 45 Wall St., Julofsky handed his satchel over to the other messenger to go in and wash his hands at 71 Broadway. The other messenger waited”¦and waited”¦and opened the satchel. It was empty. Julofsky, and $141,000 ($1,676,761 USD2007) were gone.

Julofsky rented an apartement on East 38th, just off Madison Ave. for a month, and then headed west. He met an ex-policeman named John J. Stoney in a Detroit YMCA and they began to travel together. (In answer to a question about girls, he was adamant that no girls were mixed up in the plot whatsoever. Make of that what you will.) Julofsky and Stoney were shacked up together at the Auditorium when Julofsky was nabbed in the lobby on December 27. “I don‘t know why I did it,” said the son of a retired cloak and suit maker, “no girls were mixed up in it and no one is to blame but myself.” He was given three years and change in Sing Sing. He won‘t be alone, though, as his brother Milton and a bond dealer from the Bronx named Arthur Miller were also sent up for criminally receiving his bonds.

Julofsky rented an apartement on East 38th, just off Madison Ave. for a month, and then headed west. He met an ex-policeman named John J. Stoney in a Detroit YMCA and they began to travel together. (In answer to a question about girls, he was adamant that no girls were mixed up in the plot whatsoever. Make of that what you will.) Julofsky and Stoney were shacked up together at the Auditorium when Julofsky was nabbed in the lobby on December 27. “I don‘t know why I did it,” said the son of a retired cloak and suit maker, “no girls were mixed up in it and no one is to blame but myself.” He was given three years and change in Sing Sing. He won‘t be alone, though, as his brother Milton and a bond dealer from the Bronx named Arthur Miller were also sent up for criminally receiving his bonds.

The Lobby of Convergence:

The Auditorium Hotel features itself in a roundabout way as a minor footnote in the famous 1922 Klan raid of Volstead-violating Mexicans in Inglewood, wherein a police shootout ended up in the cops shooting–guess what!–three of their own, one fatally (the town constable), discovered only when the hoods were opened.

In the depths of the lengthy trial, a stylishly dressed woman began to moan loudly, and when the bailiffs attempted to escort her out, she twisted and fought and screamed “Help! Help! Help! Let me go, I want to see a Kleagle, I want to see a Kleagle!” in tones so loud it brought people out from several floors above and below. She was carried out fighting and taken to the psychopathic ward for observation. Found in her handbag? Her Auditorium Hotel room key. (FYI, the Kleagle there at the time was Nathan A. Baker, then a deputy sheriff for Los Angeles County.)

In the depths of the lengthy trial, a stylishly dressed woman began to moan loudly, and when the bailiffs attempted to escort her out, she twisted and fought and screamed “Help! Help! Help! Let me go, I want to see a Kleagle, I want to see a Kleagle!” in tones so loud it brought people out from several floors above and below. She was carried out fighting and taken to the psychopathic ward for observation. Found in her handbag? Her Auditorium Hotel room key. (FYI, the Kleagle there at the time was Nathan A. Baker, then a deputy sheriff for Los Angeles County.)

And for the last time, that‘s Kleagle, not Fleegle.

February 7, 1923. P. C. Steckel, a boilermaker, and prominent in organized-labor society, was in court today, telling the judge a tearful story all about how he‘d been awarded the Carnegie medal of honor for rescuing some child from an oncoming train. The judge took this in, told Steckel that Scheherazade had nothing on him, but that it had precious little to do with violating the Miller-Jones narcotic law. Seems Steckel sold four ounces of morphine to a narcotics enforcement officer at the Auditorium Hotel. Nevertheless, Judge Bledsoe said that Steckel was due some consideration for possession of the medal, and gave him only two years at McNeill Island instead of the customary four.

February 7, 1923. P. C. Steckel, a boilermaker, and prominent in organized-labor society, was in court today, telling the judge a tearful story all about how he‘d been awarded the Carnegie medal of honor for rescuing some child from an oncoming train. The judge took this in, told Steckel that Scheherazade had nothing on him, but that it had precious little to do with violating the Miller-Jones narcotic law. Seems Steckel sold four ounces of morphine to a narcotics enforcement officer at the Auditorium Hotel. Nevertheless, Judge Bledsoe said that Steckel was due some consideration for possession of the medal, and gave him only two years at McNeill Island instead of the customary four.

Then there was the matter of Charles Harris, whom you remember as owner-operator of the Auditorium in the 20s and orchestrated its change into the San Carlos, tossing Rev. George Chalmers Richmond out on his ear. Harris entered Richmond‘s chamber on January 3, 1923, removed the pastor‘s clothes and by force of threats kept him from his room. Richmond alleged his good reputation had been damaged and sued for $15,000. We don‘t know what raised Harris‘s ire, though we can speculate: Richmond was a defrocked Episcopal rector, Bolsheviki refusenik and IWW nogoodnik, and mortal enemy of Methodist “Fighting Bob” Shuler. The Auditorium did have Methodists as neighbors, after all. (Why then he elected to rename the place San Carlos, which would vaguely reference some guy named Charles canonized by Papists, is beyond me.)

The Auditorium was also an exhibition hall, of sorts. It was where you‘d go in 1925 if you wanted to see, on display, Frank Prevost‘s decoding machine. Weighing only half a pound, but with a limitless capacity for sending mechanically coded messages, it represents twelve years of study and effort. See it at the Auditorium before it‘s snapped up forever by the War Department!

The Auditorium was also an exhibition hall, of sorts. It was where you‘d go in 1925 if you wanted to see, on display, Frank Prevost‘s decoding machine. Weighing only half a pound, but with a limitless capacity for sending mechanically coded messages, it represents twelve years of study and effort. See it at the Auditorium before it‘s snapped up forever by the War Department!

Also, go visit Bill Bonelli at his (1932) HQ in the San Carlos, where he‘ll enlist you in his cause against snooperism:

So what became of this wonderland of wonders, you ask?

The San Carlos crept her way into the Future, turning her back on the demolition of Bunker Hill behind.

Then, in 1983, David Houck, president of Auditorium Management Co., which purchased the Philharmonic from Temple Baptist, announced demolition to make way for a new office building, hotel and residential condominiums. (Interesting management style, and it remains a parking lot.) Physicians Pharmacy, which opened in the Auditorium Office Bldng. in 1906, moved its vast pharmacy museum–endless Edwardian prescription books, grinders and corkers, bottles full of arcane lotions and potions–across Olive to the San Carlos. That was a bad move: the San Carlos‘s days were numbered.

What‘s there to tell? Somewhere around 1987 the corner was cleared. Not a word in the papers to mark its passing. Nobody cried for First German Methodist, either.

The Southern California Gas Company thought their headquarters would be nifty there.

Richard Keating of Skidmore, Owings and Merrill thought it would be cool to design the top to look like a blue flame. Which it sort of does. At least you can eat at their Blue Flame cafeteria.

Why its crown does not light up blue at night is a mystery to all.

In any event, it is finished in 1991.

That then is the tale of the Auditorium/San Carlos Hotel.

Walk in the Gas Co. tower sometime and ask for the Wyatt Earp suite, you’re late for the faro game.

Images courtesy Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection, USC Digital Archives, and California State Library; postcards, author, except Auditorium lobby, for which I owe my usual debt to Brent C. Dickerson; sleek shots of the Gas Co. Tower from the sleek e-brochure found here; tower under construction photo from the skyscraperpage forum; and the Earp images are just all over the place.

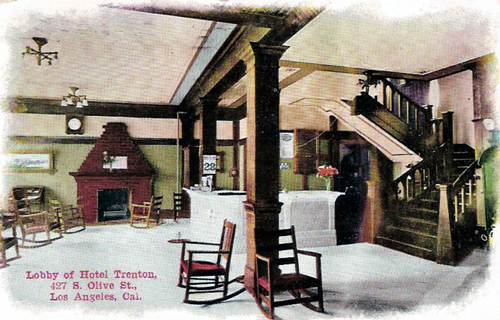

Hotel Trenton, 427 South Olive Street

The Hotel Trenton, seven stories of sober brick laced with fire escapes, its yawning central maw somewhere between a gate of hell and a jaunty fireman’s doorway, lurked low on Bunker Hill for many decades. There it is at 10 o’clock in the panorama. It was not a racy hotel, but it had its moments, and left an imprint on the fabric of its times.

And speaking of imprints, it was July 1905 when a lady guest of the establishment marched into to the Los Angeles Times offices to report her dismay at having ruined her long white skirt, white stockings and slippers when she walked over the streetcar tracks at First and Broadway and picked up a liberal helping of petroleum, which the cars’ operators had smeared on the rails to deafen the screech which otherwise came whenever a curve was taken. A snarky Times reporter noted that had the lady been as eager to lift her skirts when crossing the tracks as she was to show off the damage caused by the oil–"and it’s higher up, too!"–she would not be in such a predicament.

In May 1906, town gossips received confirmation of a scandal, but too late to shun anyone involved. Some months earlier, Mrs. Genevieve Hughes arrived in Los Angeles from Denver and took rooms in the Trenton, where she was paid significant attention by fellow guest, Boston lawyer Charles W. Ward. Ward was briefly a Harvard man who took his degree from Columbia, a gymnast, a Knight Templar and a soldier, every inch the eligible young fellow… well, almost. Again and again he would ask that she marry him, and always she would demur–but not refuse his friendship. On February 28, Ward went into his room and shot himself in the head, and the whispers said it was out of thwarted love for Genevieve. The lady, however, had eyes for another, and quietly married A.G. Jones, also of Boston, departing for an Eastern honeymoon before news of the nuptials spread. And as for Ward, he was, it proved, a bounder, having left a wife and children awaiting the return of his health under the Californian sun. He lingered a few days after being shot, but died before his father could arrive by train.

In November 1907, Mexican Secret Service officer (and soon-to-be fink in the trial of revolutionary countrymen Magon, Rivera and Villareal) Trinidad Vasquez left the safe harbor of the Trenton for a meal in a restaurant at Fifth and Olive. He had a ham and cheese sandwich and a cup of coffee, returned to the hotel and walked out again. In front of the Police Station, Vazquez was stricken with symptoms of poisoning and rushed to Receiving Hospital, where his stomach was pumped. Relieved, Vasquez testified that soon after eating he had felt a sense of suffocation, then felt as though his very heart would burst before blackness washed over him. He was soon released, doubtless with a greater respect for the fervor of the anarchist community of Los Angeles.

In early February 1909 it was revealed that the Trenton’s recently hired night clerk Harry Stevens was in fact Florin G. Lee, a Riverside lad who’d suffered a breakdown from overwork (dry goods clerking by day, electrical engineering study by night) or, some whispered, love unrequited, on December 30 and fled his home, shaking off all memory of his former life. When confronted by old friends, who said they knew him well, Stevens/ Lee expressed astonishment, and mused on his happier times in Iowa and Butte, Montana, and his New Years Day rail trip to Los Angeles over the Salt Lake Route. Conveyed to Riverside, he looked with bemusement upon his aged grandmother and treated the rest of the family with cordial unfamiliarity. He did not recognize the shop where he clerked for nine years, the books he had kept (quite well) or respond to the music which he formerly had loved. For two months, the stranger stayed on in Riverside as those who loved him tried to spark a memory of his past life. And then suddenly, on April 2, while in the dry goods store where he had long labored, Florin’s memory of his accounting work came flooding back. He raced to San Bernardino to share the happy, mathematical news with his father, and we hear no more about him.

On the evening of August 6, 1912, an "elevator pilot" was sent down to the basement to fetch some ice water. On the way up poked he his head out as the cage made its ascent. The ice water went everywhere, and so did the poor lad’s cranium. So complete was the destruction that there was initially some confusion when night clerk E.G. Merrifield came on the scene as to whether the dead man was Charles J. Oberman or his colleague, Earl Ansley. The victim was actually, it transpired, Earl McDonald, 18, from Riverside, who was moonlighting under the name Earl C. Ansley at the Trenton and working a day shift at the Hotel Victoria at Seventh at Hope. It was his first night on the job, and hotel manager R. Hughes was later charged for violating the state law requiring all elevator operators be properly licensed.

On February 3, 1913, S. W. Westmeyer, a successful mining man from Globe, Arizona, visited his wife at the Trenton and wrote her a check for $1025. From there, he went to the Hotel Redondo in Redondo Beach, where, the following evening, he shot himself in the head. Westmeyer left notes giving his personal effects to his wife and asking that his Lodge, Rescue No. 12 of the International Order of Odd Fellows in Globe be notified of his passing.

Later that month, the Trenton figured in the notorious jury tampering case of the great attorney Clarence Darrow, who rang up large charges at the hotel for select jurymen, far in excess of the $9 weekly rate that investigators were quoted–though it was the thirty dollars in ten cent cigars that got the jury’s goat.

In October 1915, resident Marie Kinney announced that she was moving her dressmaking parlor from the Fay Building at Third and Hill to the Trenton, and noted that help was wanted. A year later, she announced her winter reopening in suites 102-103-104, crowing "choicest novelties in stock." Marie must have liked the place, for it was still her home on Valentine’s Day 1941, when, aged 80, she stepped in front of a Pacific Electric car on Huntington Drive near Poplar in El Sereno, and was killed instantly. Her rosary was said at Cunningham & O’Conner at 1031 South Grand, requiem mass held at St. Vibiana’s and she was interred at Calvary.

In October 1917 the Los Angeles Division of the Collegiate Periodical League began a monthly drive to collect 5000 magazines, none older than ten days, for distribution among the servicemen at Camp Lewis. Among the district captains was Mrs. Alice M. Bryant of the Hotel Trenton. Your blogger will now attempt to staunch the drool inspired by the thought of what was gathered.

Late on December 2, 1930, the Trenton was among a trio of downtown hotels robbed by a pair of bandits in a taxicab. After they hit the Stillwell at 9th and Grand for $30 and a pair of guest handbags, unknowing driver George Kruger waited patiently outside the Trenton while night clerk A. E. Finnity and manager Herbert Perry were relieved of another $30. Finally the Victor Hotel at 616 South St. Paul was victim, and again yielded up a lucky thirty simolians. The thieves then paid their ferryman and slipped off into the night.

By 1933, we note that rooms were being let for a modest $3.50 a week. On June 8, 1936, Arnie J. Powers, 42, shot himself to death in his room, having failed to recover his health after coming out from Omaha.

On June 14, 1937 the Trenton hosted its most eloquent suicide, when retired schoolteacher Mrs. Ida Mae Mills, 70, gassed herself with a chloroform-soaked rag alongside an open copy of the book The Right to Die. Her note read, "Remember this–Death should be a smooth finish, not a jagged interruption. There is nothing mysterious nor dramatic about this. Neither was it conceived in a moment of desperation. I think I am as sane as I ever was, but I have long been convinced of the wisdom of mercy killing. Why must I live on, tortured by constant pain, and facing total blindness? My abject apologies to the management for the trouble I am giving them, but I had to have some place to die, didn’t I? I could not vanish into the air."

She could not, but sometime in the early 1960s, it seems, the Trenton Hotel did just that. We can only assume the CRA had a little something to do with that.

Postcards from the Nathan Marsak Collection, Vasquez and 1908 advertisement from the Los Angeles Times, panoramic photo from the Los Angeles Public Library.

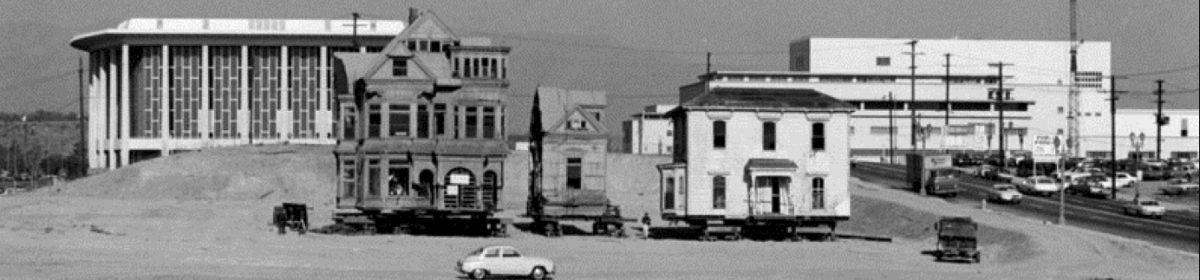

The Monarch

As has been noted, when it comes to Bunker Hill, there is no image as iconic as Union Bank Square–the Redevelopment Project‘s first great endeavor–towering over remnants of antiquated Los Angeles. (One could argue there are few sights as telling when it comes to defining Los Angeles in general.) But while we‘re all familiar with those 42 stories of mid-60s glory, who remembers what stood there before? It was that hitherto unsung monument of Los Angeles deco: the Monarch Hotel.

As has been noted, when it comes to Bunker Hill, there is no image as iconic as Union Bank Square–the Redevelopment Project‘s first great endeavor–towering over remnants of antiquated Los Angeles. (One could argue there are few sights as telling when it comes to defining Los Angeles in general.) But while we‘re all familiar with those 42 stories of mid-60s glory, who remembers what stood there before? It was that hitherto unsung monument of Los Angeles deco: the Monarch Hotel.

The Monarch opened in mid-October, 1929. It contained sixty-six hotel rooms, fourteen single apartments, twelve double apartments, a five-room bungalow on the roof, three private roof decks planted rich with shrubbery, and a lobby embellished with hand-decorated ceilings. It was entirely furnished by Barker Brothers with furniture of “modern type and design.”

From the outset, crime dogged the Monarch. Sort of. The first occupants of the bridal suite, in November 1929, were Motorcycle Officer Bricker of Georgia-Street Traffic Investigation and former Miss Losa Pope (the now newly-minted Mrs. Bricker, a purchasing agent at Forest Lawn).

They met when he had arrested her for speeding. On their first morning together as Man and Wife, breakfasting on the roof garden outside their bridal suite, they were mobbed by twenty some-odd members of the Force who decided to burst in and make merry with fellow officer and his tamed scofflaw.

Real crime did, in fact, visit upon the Monarch. (This may have had something to do with opening two weeks before the Crash.) For example:

Night clerk H. N. Willey was behind the desk at the Monarch when, just after midnight on June 16, 1930, a bandit robbed him of $26. Willey phoned Central Station. Meanwhile, officers Doyle and Williams, on patrol, observed a man hightailing it through an auto park near the hotel. Deciding that he wasn‘t running for his health (this being some years before the jogging craze), they gave chase and caught him in an alley. They next observed a patrol car flying to the Monarch. Putting two and two together, they took their prisoner to the hotel, where he was id‘d by Willey. Turns out he was George H. Hall, 24, a recent arrival in Los Angeles.

Night clerk H. N. Willey was behind the desk at the Monarch when, just after midnight on June 16, 1930, a bandit robbed him of $26. Willey phoned Central Station. Meanwhile, officers Doyle and Williams, on patrol, observed a man hightailing it through an auto park near the hotel. Deciding that he wasn‘t running for his health (this being some years before the jogging craze), they gave chase and caught him in an alley. They next observed a patrol car flying to the Monarch. Putting two and two together, they took their prisoner to the hotel, where he was id‘d by Willey. Turns out he was George H. Hall, 24, a recent arrival in Los Angeles.

H. N. Willey continued to ply the night clerk trade, and was doing so when two men entered on the early morning of August 31, 1931. When Willey showed them to their room, they pulled out a gun and tried to lock him in the closet. The attempt failed because the door had no outside lock, so the hapless crooks ran downstairs, recovered the $2 they had paid for the room and fled.

H. N. makes the papers again in November of 1931, when on the Wednesday before Thanksgiving Los Angeles is hit by a massive crime wave, in which over a dozen brazen robberies of hotels, groceries, theaters, pedestrians, folks in autos, etc. are shot at and robbed; Willey looks down the barrel of a large-bore automatic and forks over $25.

One thing that‘s nice about the Monarch? It‘s nice to have a bar downstairs. Edgar Lee Smith lived, and drank, at the Monarch.

August 23, 1946. Smith, 51, had been drinking in the Monarch bar but neglected to keep to the cardinal rule of always keeping on the good side of one‘s bartender. This resulted in an after-hours duel that left his bartender, James Donald Chaffee, 28, stabbed to death. When the Radio Officers Hill and Finn found Chaffee‘s body on sidewalk, they went to Smith‘s room, where they found him changing his clothes, and seized a penknife with a one-inch blade.

The fight began when, according to Smith, “Jimmy got sore because I stole his girl.” Smith added that barkeep Chaffee, in retaliation, cut Smith off. Smith, in counter-retaliation, cut Chaffee.

Smith plead guilty to manslaughter and was sentenced to one to ten in San Quentin.

Gilbert Carvajal was a 17 year-old Marine stationed at Del Mar, part of Pendleton. He was at the Monarch on May 9, 1957, with his 45 year-old lady-friend Frances Nishperly when it all began. It was 1:15am and he decided it wise to hold up night clerk Frost E. Stacklager (H. N. Willey having retired, apparently) and make off with $22 and jewelry. A few minutes later the two robbed the Trent Hotel of $57.50; despite holding the clerk at knifepoint, the two next fled the Floyd Hotel empty-handed, but snagged $45 from the till at the Auto Club Hotel minutes later. At 23rd and Scarff Sts. the police began shooting into Carvajal‘s car–he tried to make a run for it but was shot down in the street, taking one to the chest. Ms. Nishperly insisted Carvajal had kidnapped her from the corner of Pico Blvd. and Hope St., but police elected to discount this story.

Now, people are forever plunging off the precipices afforded by tall structures (a quick peruse of On Bunker Hill proves that) and that‘s a person‘s right and due. But it‘s different when it‘s an excited doggy.

Buddy was one such excitable pooch, who went nuts and ran right off the top of the Monarch Hotel! Of course the Hand of God intervened, and Buddy–a 2 year-old fox terrier–fell one hundred feet, landing atop an auto roof, but emerged without a scratch, May 1, 1931. (Apparently Buddy had landed on one of the small unbraced portions of the auto top; parking station attendants ran out when they heard a windshield smash and found a confused dog standing on top the machine, looking for a place to descend.)

Buddy‘s daddy, Jimmy Van Scoyoe, was looking frantically for his pooch and had no idea of his aerial adventure when he peered off the roof and saw his Buddy surrounded by a puzzled crowd. Jimmy is reported to have tightly clasped Buddy in his arms and vowed to never let him out of his sight again “even if I have to keep him in bed with me when I go to sleep.” Damn straight!

Lead architects on the Monarch are Cramer & Wise, who did pioneering auto-culture work with their 1926 “Motor-In Markets”–one at the NW corner of First and Rosemont (above, demolished 1962) and another at the NW corner of Sunset and Quintero (still there, vaguely recognizable):

Lead architects on the Monarch are Cramer & Wise, who did pioneering auto-culture work with their 1926 “Motor-In Markets”–one at the NW corner of First and Rosemont (above, demolished 1962) and another at the NW corner of Sunset and Quintero (still there, vaguely recognizable):

One can also go visit Cramer & Wise’s Van Rensellear Apartments,

SE corner of Franklin and Gramercy”¦  …of course, what they‘re best known for is La Belle Tour.

…of course, what they‘re best known for is La Belle Tour.

Consulting architects on the Monarch were Hillier & Sheet, probably best known for Beverly Blvd. landmark the Dover.

While Mediterranean in manner, their 1929 complex on the NE corner of McCadden and West Leland Way is mysteriously named the Aloha.

While Mediterranean in manner, their 1929 complex on the NE corner of McCadden and West Leland Way is mysteriously named the Aloha.

This 1929 31-unit Mediterranean complex in the Wilshire District still stands:

But this one on El Cerrito was demolished; an 80s building of unusual blandeur has taken its place.

Hillier & Sheet announce this height-limit Norman job will go up at Fountain and Sweetzer; it does not materialize.

S. Charles Lee‘s El Mirador, though, does.

Who loves the lost Monarch? People are quick to fetishize the felled Richfield Tower, and with good reason (I, too, am an ardent obsessive–even owning parts of it); but isn‘t it a bit”¦New York? Doesn‘t it owe a major debt to Hood‘s American Radiator Building? Sure, some might argue that the Streamline Moderne is more natively Angeleno, but not only was that industrial-inspired application an Internationalist movement, but one also feels in its nautical element a particular evocation of our neighbor to the north, San Francisco.

What is elementally endemic to the land, here, is the Ziggurat Moderne of the Monarch Hotel–that there is something in the setback style that elicits a feeling for the indigenous, the “really” American, in that the mock-Mayan comes closest to the true architecture of this part of the world. The core of this argument comes, of course, from Francisco Mujica‘s 1929 History of the Skyscraper, where he hints at just that–that pre-Columbian pyramids are the correct expression of modernity, and vice versa (hence the natural evolution of the 1916 New York setback laws”¦glorious mother of what Koolhaas termed the Ferrissian Void).

Thus–where one might see the Monarch as somewhat squat:

…we should take that as monumentality in its most impressive (if not oppressive, if that‘s what reverberates in your Incan blood) form.

1906, the NW corner of Fifth and Figueroa at bottom right:

1950, twenty years after the installation of the Monarch:

1953, with the addition of the Harbor Freeway:

After fifteen years of Sturm n Drang, on February 3, 1964, the $350 million Bunker Hill Urban Renewal Project got its first bite–Connecticut General Life offered $3.3 million for the block-square site that housed the Monarch Hotel.

CRA Chairman William T. Sesnon Jr., expressed his elation: “The sale is virtually completed. We are overjoyed by this development. It‘s our hope it will serve as the real kickoff for the entire Bunker Hill project.”

Thirty days later–March 4, 1964:

On March 30, 1965, red-jacketed attendants ushered dignitaries under a white-fringed canopy, where they watched a bulldozer tear up some concrete. “Welcome to Bunker Hill–at last,” proclaimed Sesnon. “This is the start of something dramatic.”

Some of the luster of Sesnon‘s kickoff was dulled when in 1966–with the Union Bank half built–City Administrative Officer C. Erwin Piper and his staff issued a scathing report on the CRA. It sited faulty operational control, an absence of clear-cut policies and poor internal coordination, at terrific taxpayer expense. By the end of 1967 no more land had been disposed of, the CRA had lost half its department heads, had no executive director, and Sesnon had been replaced by Z. Wayne Griffin.

The Battle of Bunker Hill would continue to be waged–that long, slow, protracted engagement, which like its previous fifteen years, would need another fifteen years before things shifted into high gear again.