Folk will on occasion ask me what, if anything, is left of Bunker Hill. Glad you asked, I‘ll reply, answer being, nothing really, but I am awfully fond of this particular dirt contour. If they don‘t politely turn away, I‘ll commence upon a detailed discourse on said excrement-laden dirt contour in question, and then they‘ll politely turn away.

Strange as it sounds, I love this dirt. I have since I was one day idling in my auto adjacent this, the northwest corner of Second and Hill, when I saw this form and it recalled an image lodged in some dim grotto of my brain:

And I thought, I know that form. That contour. Like a beautiful woman in repose. Debased somehow, but still noble. Ingres‘ Odalisque has become Manet‘s Olympia.

So here I am in pith helmet and plus-fours, poking around the strangely stained abandoned sweatpants and taking in the stench of urine steaming away on a hot summer‘s day. My own Persepolis, only with more recent death and egesta. A remaining honest remnant of Bunker Hill, carved in dirt. There‘s an old Yiddish proverb–Gold‘s father is dirt, yet it regards itself as noble.

Let‘s take a detailed look at the block our patch of dirt calls home.

In 1888, on the 30-40′ bluff overlooking Hill there’s a large house, center, and another (with a “old shanty”, it is noted) at the corner of Second and Hill. The round structure above the house on the right reads “arbor lattice.” Note the porches on the Argyle.

1894, and 133 Hill has built terraced steps up to its manse. Our house in the corner has sadly lost its shanty. Notice the addition of the Primrose hotel at 421/419 West 2nd. At the bottom it reads “Vertical bank 30‘ high.” The house near 1st has been razed but 109 Hill has been added. 104 Olive has shown up, top right. And yes, that says “Lawn Tennis Courts.”

It‘s 1906, and much has changed: our little friend in the corner has disappeared. In its place, just to the north, two lodging houses at 411 and 409. To the west, Hotel Locke. (Hotel Locke shows up in the Times in 1897 and disappears in 1912.) Olive Court has wrapped around and filled in, and the tennis lawn has given way to our old friend the Moore Cliff. The former single family dwelling at 109 has been enlarged to become the El Moro Hotel. Note the Hotel Cecil in the upper right. Hill now has a 15‘ retaining wall; the houses average 30‘ above grade.

But now it‘s 1950 and the drastic has occured. Where once Second Street was sixty feet across, it is now 100, due to the construction of the Second Street tunnel, which opened in July of 1924. (As Mary mentioned in her post, the Argyle lost its porches.) Also lost were the two structures below the Primrose at 411 and 409, not to mention the Hotel Locke. These were even gone before the great excavation. The Hotel Cecil has, as you might imagine, been renamed, so as not to be confused with the Hotel Cecil. We even have a little gas station.

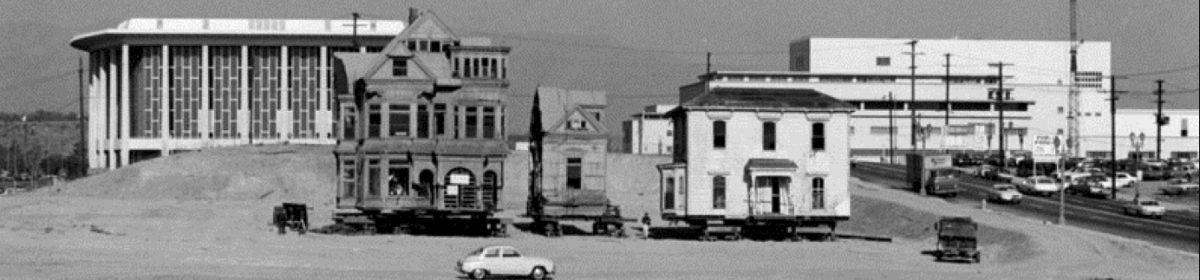

In a nutshell, ca. 1952: the Moore Cliff front and center, the bipartite El Moro, and the Hotel Gladden up the block in the corner. And there‘s the Texaco station that popped up. (Faithful Bunker Hillers will recognize the looming backside of the Melrose Annex and the Dome up top.)

But back to the “great excavation.” Remember, once Hill had, well, a great hill looming o‘er. It was true here, at our corner in question:

What happened to the giant pile of dirt (upon which 411 and 409, and the Hotel Locke once

sat) as seen in the 1932 photograph?

As can be barely viewed just below the Moore Cliff in the ‘32 shot, a lot fronting Hill has already been excavated for auto parking, and in May of 1935 the two adjacent lots at the corner were leveled by Los Angeles Rock and Gravel, removing 40,000 cubic yards of earth adjoining the tunnel ramp, measuring some 45hx82wx157d’. One lot owner, C. J. Heyler, rented the space to P. F. Drino for automobile parking; Heyler stated that construction on the lot was planned. That, of course, never happened.

This, then, is how we ended up with Hill carvings that have remained unchanged for seventy-three years.

And still fulfilling the same purpose.

Looking southeast at our dirt, 1967, before her Hill Steet side had her top shaved off:

A quick word about the Second Street tunnel–with the millions the CRA is again pouring into Bunker Hill, do you think we could throw a few bucks toward a new railing? To refashion the original concrete couldn‘t run that much, and if not an aesthetic improvement, would be arguably safer than chain link. Right?

Thank you in advance for your attention to this matter.

In any event, such is the tale of some simple dirt on a single block. Tune in next week for tales of terror as they relate to this part of the world.

And now, you can launch into your own spiel about the dirt contours of Hill Street. I suggest a visit and have a whiff for yourself of what once was Bunker Hill. Serves to add that dose of realism guaranteeing the polite turning-away of cocktail party folk.

Images courtesy Arnold Hylen Collection, California History Section, California State Library and USC Digital Archives; special thanks of course to D. A. Sanborn, his map company, and the anonymous field men who toiled on the fire insurance maps Sanborn Co. produced.

…which suffices only until she can fashion a thirty-nine unit brick apartment complex in 1908. She lives therein until she dies of cerebral hemorrhage in 1926; she leaves an estate valued at $300,000 ($3,521,554 USD2007).

…which suffices only until she can fashion a thirty-nine unit brick apartment complex in 1908. She lives therein until she dies of cerebral hemorrhage in 1926; she leaves an estate valued at $300,000 ($3,521,554 USD2007).

Zelda wasn‘t the only wealthy woman to die in the Zelda–Baroness Rosa von Zimmerman, who with her husband the Baron were second only to Krupps when to it came to weapons manufacturing for various Teutonic scraps, lived at the Zelda and died there, an alien enemy, in 1917, leaving Rosamond Castle, on fourteen acres,

Zelda wasn‘t the only wealthy woman to die in the Zelda–Baroness Rosa von Zimmerman, who with her husband the Baron were second only to Krupps when to it came to weapons manufacturing for various Teutonic scraps, lived at the Zelda and died there, an alien enemy, in 1917, leaving Rosamond Castle, on fourteen acres,  Yes, there’s never a lack of excitement at the Zelda. Take by example the May 1916 discharge of Zelda‘s porter George “an erratic Japanese” Nakamoto. Having been sacked by La Chat, and replaced by one K. Kitagawa, Nakamoto saw fit to return to the Zelda to seek out his successor. There was Kitagawa, crouched low, tacking down oilcloth in a cubbyhole beneath a stairway; Nakamoto grabbed a riveting hammer and struck him repeatedly on the head, injuring his skull, and sending him to Receiving hospital in critical condition.

Yes, there’s never a lack of excitement at the Zelda. Take by example the May 1916 discharge of Zelda‘s porter George “an erratic Japanese” Nakamoto. Having been sacked by La Chat, and replaced by one K. Kitagawa, Nakamoto saw fit to return to the Zelda to seek out his successor. There was Kitagawa, crouched low, tacking down oilcloth in a cubbyhole beneath a stairway; Nakamoto grabbed a riveting hammer and struck him repeatedly on the head, injuring his skull, and sending him to Receiving hospital in critical condition. And then there was the night of March 10, 1939, when vice squads in Los Angeles in Beverly Hills came down on bookmaking establishments; seventeen were arrested, including James Adams, 48; George Taylor, 24; James Roberts, 26; Mrs. Agnes Meyers, 36, and Yvonne Lucas, 21, whom Central Vice took offense to the making of book in an apartment at the Zelda. (Interestingly, across Hollywood and Beverly Hills, the pinched bookmakers more often than not had names like Murray Oxhorn and Morris Levine and Saul Abrams and Joseph Blumenthal; could our Zelda perchance have been a bit”¦restricted?)

And then there was the night of March 10, 1939, when vice squads in Los Angeles in Beverly Hills came down on bookmaking establishments; seventeen were arrested, including James Adams, 48; George Taylor, 24; James Roberts, 26; Mrs. Agnes Meyers, 36, and Yvonne Lucas, 21, whom Central Vice took offense to the making of book in an apartment at the Zelda. (Interestingly, across Hollywood and Beverly Hills, the pinched bookmakers more often than not had names like Murray Oxhorn and Morris Levine and Saul Abrams and Joseph Blumenthal; could our Zelda perchance have been a bit”¦restricted?) Marcelino had also attempted to lift a safe and had lost part of his fingernail in the process–the cops found they had the perfect match.

Marcelino had also attempted to lift a safe and had lost part of his fingernail in the process–the cops found they had the perfect match.

March 31, 1912

March 31, 1912

What do you notice here, from this 1932 image of the Moore Cliff?

What do you notice here, from this 1932 image of the Moore Cliff?

Today we discuss The Marcella, who once flaunted her classical order on Flower (she is Italian, please be advised the C in her name is not pronounced s as in sell, but like ch as in chin). See how her name beckons, proud but not haughty, from her entablature? She wants to take you in and protect you under that great cornice with her large corbels. Despite her imposing presence, she is warm, and welcoming; the wide porches bespeak grace, and the timberframe vernacular on the bays coo cozy by the fire lad, there‘s good feelings in mortise and tenon.

Today we discuss The Marcella, who once flaunted her classical order on Flower (she is Italian, please be advised the C in her name is not pronounced s as in sell, but like ch as in chin). See how her name beckons, proud but not haughty, from her entablature? She wants to take you in and protect you under that great cornice with her large corbels. Despite her imposing presence, she is warm, and welcoming; the wide porches bespeak grace, and the timberframe vernacular on the bays coo cozy by the fire lad, there‘s good feelings in mortise and tenon.

After our initial report on

After our initial report on

March 11, 1961. Alfred Carrillo, 33, was a Dome resident in good standing who had the bad luck to be sitting in a bar at 301 South Hill Street one early Friday morning. Victor F. Jimenez, 26, unemployed truck driver, shot Alfred and then drove off, later to be arrested at his home. (The bar at 301 South Hill, by the way, was the bar at the base of Angels Flight–seen here with Lon Chaney Jr. in the 1956 outing

March 11, 1961. Alfred Carrillo, 33, was a Dome resident in good standing who had the bad luck to be sitting in a bar at 301 South Hill Street one early Friday morning. Victor F. Jimenez, 26, unemployed truck driver, shot Alfred and then drove off, later to be arrested at his home. (The bar at 301 South Hill, by the way, was the bar at the base of Angels Flight–seen here with Lon Chaney Jr. in the 1956 outing

Worthing was a statuesque Bostonian-by-way-of-Kentucky who‘d become a Ziegfeld Follies girl–the toast of New York, and lady-friend of a New York mayor, it was said. Darling of the rotogravure section, it was then on to Hollywood, where she made pictures galore while at the same time gracing nightly Ziegfeld‘s well-known assemblage of pulchritude.

Worthing was a statuesque Bostonian-by-way-of-Kentucky who‘d become a Ziegfeld Follies girl–the toast of New York, and lady-friend of a New York mayor, it was said. Darling of the rotogravure section, it was then on to Hollywood, where she made pictures galore while at the same time gracing nightly Ziegfeld‘s well-known assemblage of pulchritude.

They keep the wedding secret but is revealed to the world late in 1929, after their estrangement becomes known. His philandering, cruelty, jealously, and threats of confining her to some sort of institution are apparently too much for her.

They keep the wedding secret but is revealed to the world late in 1929, after their estrangement becomes known. His philandering, cruelty, jealously, and threats of confining her to some sort of institution are apparently too much for her.  On August 16, 1933, the coppers come to The Sherwood to collect Helen Lee Worthing on violation of her parole to the psychopathic department. In a statement from her psych ward bed at General Hospital, Helen declared that she had been living quietly in her apartment, attempting to increase her income by writing poetry and short stories. “I can‘t understand who would complain and have me returned here,” she said. “I have only been trying to get a start on my own ability. Incidentally, I have fallen in love with a man who has been typing my poetry, but that has nothing to do with this.”

On August 16, 1933, the coppers come to The Sherwood to collect Helen Lee Worthing on violation of her parole to the psychopathic department. In a statement from her psych ward bed at General Hospital, Helen declared that she had been living quietly in her apartment, attempting to increase her income by writing poetry and short stories. “I can‘t understand who would complain and have me returned here,” she said. “I have only been trying to get a start on my own ability. Incidentally, I have fallen in love with a man who has been typing my poetry, but that has nothing to do with this.”

In 1946 she‘s found downed and dazed at

In 1946 she‘s found downed and dazed at

When

When  December 28, 1918. Juvenille officers were called to a vacant lot at First and Hope where young toughs were blasting away at tin cans with their air rifles. The two collared ringleaders were on their way to the station house when one of the youngsters tucked a lock of long hair under his cap”¦he being Miss Juanita Stuart, fourteen, of the Rossmere. She protested tearfully when her mother was instructed by officers to burn the costume of khaki trousers, flannel shirt and boy‘s sweater, and to keep the young lady attired in feminine apparel only thereafter.

December 28, 1918. Juvenille officers were called to a vacant lot at First and Hope where young toughs were blasting away at tin cans with their air rifles. The two collared ringleaders were on their way to the station house when one of the youngsters tucked a lock of long hair under his cap”¦he being Miss Juanita Stuart, fourteen, of the Rossmere. She protested tearfully when her mother was instructed by officers to burn the costume of khaki trousers, flannel shirt and boy‘s sweater, and to keep the young lady attired in feminine apparel only thereafter.

September 23, 1949. Lloyd E. Bitters, 82, a former shoplifter by trade, decided on September 5 of this year to stop eating. The fourteen-year resident of the Rossmere simply found life “no longer worth living,” which is reasonable enough (moreover recently-assassinated Gandhi had made fasting fashionable). But Bitters was descended upon by members of the Community Chest and the Salvation Army‘s Golden Agers Club, who bundled him up and trundled him off to General Hosptial for psychiatric examination.

September 23, 1949. Lloyd E. Bitters, 82, a former shoplifter by trade, decided on September 5 of this year to stop eating. The fourteen-year resident of the Rossmere simply found life “no longer worth living,” which is reasonable enough (moreover recently-assassinated Gandhi had made fasting fashionable). But Bitters was descended upon by members of the Community Chest and the Salvation Army‘s Golden Agers Club, who bundled him up and trundled him off to General Hosptial for psychiatric examination.  September 5, 1951. Whereas the

September 5, 1951. Whereas the  September 7, 1955. Fred H. Morales, 28, delivered a benediction of blood to six of his sleeping children. And after his sprinkler-like artery-opening anointing act, he beat down a door and chased his wife–she carrying their nine-month-old baby–and her parents into the street outside the Rossmere with a butcher knife. When the cops finally arrived at First and Hope they found Morales inside, having slashed his throat with a razor blade. He was taken to the prison ward at General Hospital.

September 7, 1955. Fred H. Morales, 28, delivered a benediction of blood to six of his sleeping children. And after his sprinkler-like artery-opening anointing act, he beat down a door and chased his wife–she carrying their nine-month-old baby–and her parents into the street outside the Rossmere with a butcher knife. When the cops finally arrived at First and Hope they found Morales inside, having slashed his throat with a razor blade. He was taken to the prison ward at General Hospital.

The history of Bunker Hill could not be written without mention of a man who stood up to face the foe. Who fought City Hall; who fought the law, and sure, the law won. But let‘s remember the man. Firebrand. Gadfly. Babcock.

The history of Bunker Hill could not be written without mention of a man who stood up to face the foe. Who fought City Hall; who fought the law, and sure, the law won. But let‘s remember the man. Firebrand. Gadfly. Babcock. But one fellow didn‘t think the idea so all-American–owner of

But one fellow didn‘t think the idea so all-American–owner of

Oil, that is. William T. Sesnon Jr., chairman of the Community Redevelopment Agency, is an oil magnate, after all. (‘Twas he who proposed the plan to finance homes for those elderly residents who had to be relocated from Bunker Hill: the City would drill on property bounded by

Oil, that is. William T. Sesnon Jr., chairman of the Community Redevelopment Agency, is an oil magnate, after all. (‘Twas he who proposed the plan to finance homes for those elderly residents who had to be relocated from Bunker Hill: the City would drill on property bounded by

This prompted some strong words on the Chamber floor, where the next day Sesnon himself stood and said in part: “I regret the necessity of speaking but the action filed yesterday makes it unavoidable. These charges are irresponsible, malicious, vindictive and utterly false. No member of the Council ever entered into such a deal. It is an outrage that we have to face such publicity and I completely resent such statements.”

This prompted some strong words on the Chamber floor, where the next day Sesnon himself stood and said in part: “I regret the necessity of speaking but the action filed yesterday makes it unavoidable. These charges are irresponsible, malicious, vindictive and utterly false. No member of the Council ever entered into such a deal. It is an outrage that we have to face such publicity and I completely resent such statements.”

May 23, 1905

May 23, 1905