After the DWP and Dorothy Chandler went up, postcard photographers said whoopee! something to shoot besides City Hall and the Chinese. So they cruised up to the bluff on Huntley, trained their lenses across Second and Beaudry toward First and Flower and fired away. The day view is a Plastichrome by Colourpicture, the night view by Western Publishing & Novelty, both circa 1965.

Dig the Union station in all its 76 ball glory (the SoCal station with its backlit chevron seems to be of an earlier vintage; they‘re both gone now). Printers shops and giant spools line Beaudry. Were it not for the necessity of capturing Becket and Martin‘s latest accomplishments, would we have any record of these? Not likely.

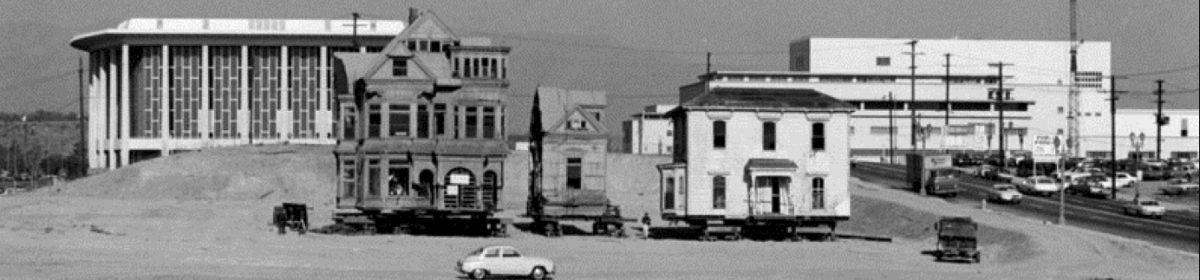

Across the Pasadena Freeway, on Bunker Hill proper, on the west side of Figueroa between First and Second, that big white structure? That‘s 123 South Figueroa, built in 1925. Whatever the most photographed buildings on Bunker Hill were–the Castle, the Brousseau, the Dome?–if there‘s another image of this structure, I‘d love to see it.

123 was erected as an office building, but in 1934 is turned into “one of the largest and most modern” government relief centers in the West. The Federal Transient Service converted the building into its Southern California headquarters, i.e., a shelter for non-resident jobless men, outfitting it with an enormous cafeteria and dormitories that slept 500. It became a veritable city in itself: showers, lockers, hospital, educational and recreational facilities were installed, as were a laundry, shoe repair and tailor shop. It was also a warehouse for materials and supplies used in the camps. Yes, the camps. Itinerant men had forty-eight hours to stay at Figueroa, max, before being assigned out of the city to transient work camps in forest and mountain areas.

Families, bands of “wild boys,” vagabonds on freight cars”¦in 1935 32,000 new transients came to California each month, 12,000 of those to Los Angeles. July of 1935 alone saw a load of 20,000 paupers arrive in LA seeking State and Federal aid. (And, one supposes, oranges that grew on palm trees.) 1,200 boys were sent to forestry camps, 4,000 men to the Federal aid camp near San Diego, but many of LA‘s transients–12% of the national and 60% of the State‘s burden–after being processed here at 123 South Fig, ended up in squatter‘s villages and squalid encampments. Many went to homes and camps, were absorbed to into County Welfare healthily, found employ in the works relief programs or went back from whence they came, but either way, it does show and say something about the class shift of the Hill that such a major locus of poverty and despair should be located within its confines.

123 is converted to the police department‘s traffic division headquarters building in 1942. The City Council gave the Police Commission $78,000 for the building and another $47,000 for the alterations.

At the dedication, during a luncheon given on the third floor, attended by Mayor Bowron, Chief of Police Horral, and numerous high ranking police officers, Deputy Police Chief Caldwell announced that Los Angeles led the nation in the decrease in auto fatalities–which occurred through “strict, scientific enforcement of driving regulations.” (Reports from 123 show that pedestrian fatalities in the first half of the 40s skyrocketed–dimouts for the war effort, don‘t ya know.)

At the dedication, during a luncheon given on the third floor, attended by Mayor Bowron, Chief of Police Horral, and numerous high ranking police officers, Deputy Police Chief Caldwell announced that Los Angeles led the nation in the decrease in auto fatalities–which occurred through “strict, scientific enforcement of driving regulations.” (Reports from 123 show that pedestrian fatalities in the first half of the 40s skyrocketed–dimouts for the war effort, don‘t ya know.)

The biggest piece of drama attached to the building came when in 1950 Parry Cottam, 27, a maintenance man at the police garage in the building, was moving a police motorcycle and it went out of control. It plunged him through a large plate-glass window on the building‘s street level, and he was found unconscious on the sidewalk.

In March of 1964, the Board of Supervisors authorized sale of the county building to the CRA. The CRA said they intended to develop the site into a motel. The garage equipment goes up for auction in April 1971 and the 123 is presumably demolished failry soon thereafterward. While the CRA didn‘t build a motel after clearing the site, the Promenade Towers have at least been described as a “roach motel.”

It‘s a $60million dollar complex, the first mixed-use apartment complex in downtown Los Angeles and the area‘s first privately owned residential rental complex. It has its formal opening June 16, 1986, the name Promenade intending to connote the era of pedestrian-oriented urbanism this project will usher in.

The Promenade becomes a favorite of Union Bank; they keep sixteen apartments there for visiting businessmen. Tommy Lasorda himself keeps a pad in the Prom. They‘re all drawn by the health club and gymnasium, market, pharmacy, dentist, café/restaurant, the 24-hour reception and valet and garage attendants and so forth.

It remains to be seen whether the 123 regains its Reagan-era splendor, or if its residents, with their dry cleaner and little shop of sundries, doesn‘t harken back to its forgotten days as a haven for homeless men and law enforcement.

1924. Emsians Jack Hart and James Whitmore were no mere bathtub gin fanciers, nor busted-at-the-speak spuds; the Feds seized Hart & Whitmore‘s forty cases of champagne, seventy-five cases of Scotch, and seventy-three cases of gin, crème de menthe and grain alcohol down at their warehouse,

1924. Emsians Jack Hart and James Whitmore were no mere bathtub gin fanciers, nor busted-at-the-speak spuds; the Feds seized Hart & Whitmore‘s forty cases of champagne, seventy-five cases of Scotch, and seventy-three cases of gin, crème de menthe and grain alcohol down at their warehouse,

1930. An employment agency sent Emsite Erma Gogleu, 16, to

1930. An employment agency sent Emsite Erma Gogleu, 16, to  1934. Emsman Joe Shaw, 26, was roaring along on his motorcycle on a Friday night down at

1934. Emsman Joe Shaw, 26, was roaring along on his motorcycle on a Friday night down at

1942. Every hotel has a suicide. And despite Harold‘s line to his Uncle Victor–“during wartime the national suicide rate goes down”–on Bunker Hill, there‘s still wartime Selbsmord (the

1942. Every hotel has a suicide. And despite Harold‘s line to his Uncle Victor–“during wartime the national suicide rate goes down”–on Bunker Hill, there‘s still wartime Selbsmord (the

1949. Joe Rupino, 50, was leaning over the railing on the second story balcony, shaking the dust from a rug, when the railing gave way and he fell fifteen feet to the pavement. Rupino received possible fractures of the right wrist, forearm and shoulder, and a trip to Georgia Street and a transfer to General Hospital.

1949. Joe Rupino, 50, was leaning over the railing on the second story balcony, shaking the dust from a rug, when the railing gave way and he fell fifteen feet to the pavement. Rupino received possible fractures of the right wrist, forearm and shoulder, and a trip to Georgia Street and a transfer to General Hospital.

The Ems is “twin tower”, á la the Santa Barbara Mission, and of course there‘s the contemporary tri-tower version a couple blocks over, the somewhat less Mission and more Moorish

The Ems is “twin tower”, á la the Santa Barbara Mission, and of course there‘s the contemporary tri-tower version a couple blocks over, the somewhat less Mission and more Moorish

The Ems and the Palace, chunks missing from their plaster, give Bunker Hill the appearance of a city pockmarked by battle.

The Ems and the Palace, chunks missing from their plaster, give Bunker Hill the appearance of a city pockmarked by battle.