In the first installment of our series on George Mann’s newly-discovered vintage Los Angeles restaurant photos, we introduced you to Mann’s custom 3-D photo viewer, which provided free entertainment to patrons as they waited to be seated in numerous L.A. restaurants, and to images of the Malibu restaurants that were displayed inside the viewers.

In mapping the restaurant exteriors that George selected to feature in his viewers, we discover he traveled widely throughout Southern California, and that when he found a subject that appealed to him, he’d explore the area looking for other sites worth photographing.

Today, let’s tag along as George immortalizes the 1950s-era dining options of the tony Bixby Knolls neighborhood of Long Beach, in a short but colorful cruise down Atlantic Boulevard.

photo: George Mann

Our first stop is Grisinger’s Drive In Coffee Shop, a classic of the Googie style designed circa 1953 by the great Wayne McAllister, and a popular stop on the teenage automotive cruising circuit of its day.

Somewhat miraculously, the elliptical stucco, brick and redwood restaurant survives as George’s ’50s Diner–but with a weird paint job and its dazzling neon script replaced by a cheesy backlit plastic car hop. The building became a Long Beach historic landmark in 2004, and perhaps one day will get the sympathetic restoration it deserves. For now, if you’ve got a hankering for biscuits and gravy and can stomach dining amidst stylized paintings of Marilyn Monroe and ledges lined with tiny pink Cadillacs, George’s kitschy counter awaits.

photo: Google street view

Diagonally across Atlantic from Grisinger’s was the famous Welch‘s, which billed itself as Southern California’s Most Beautiful Restaurant (not to be confused with The World’s Most Beautiful Restaurant, which was the slogan of The Chandelier, just one block south.

photo: George Mann

George first photographed Welch’s from the sidewalk in front of Grisinger’s (note the palm fronds), before creeping closer to immortalize the jazzy lobster-up-a-tree neon on the barrel-shaped facade–a sign we really wish he’d hung around until nightfall to capture in its illuminated glory.

photo: George Mann

photo: George Mann (detail)

And wow, what a gorgeous building! We’re struck by the overhanging walkway with its circular window onto the parking lot, a detail which leaves us wanting to see more. Happily, that hunger is partly satisfied by Maynard L. Parker’s fantastic black and white photographs of the building, in the Huntington’s collections.

Parker’s undated photographs, commissioned by architect Larry Saunders soon after completion, reveal how the barrel formed the semi-circular well of the Japanese-style cocktail bar, the meandering interior water feature dotted with aquatic flowers and, mysteriously, an apparently unbroken roof line leading out to the parking lot, while George’s undated photo shows a clear break with the sections at different heights and possibly shortened, apparently a later remodel.

photo: Maynard L. Parker, Huntington Library, Photo Archives (detail)

photo: George Mann

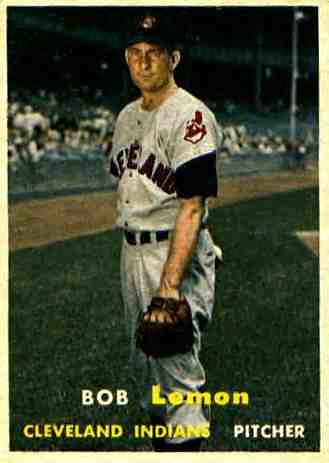

One block south on Atlantic, Bob Lemon’s Ricarts Restaurant proudly hangs the Lion’s Club medallion on its beige massing, and the standup on the sidewalk promises buffet service from 11:30 to 2. Some sort of live entertainment is on hand to aid in your digestion.

In the background, a young palm shades some buffet-skimming Lion’s Caddy, the black and gold Richfield gas station hums with activity, a handsome two-tone bus makes an awkward turn into traffic, and the Towne Theater’s proud vertical sign beams down from among the clouds.

San Berdoo-born, Long Beach-bred Bob Lemon was a right-handed pitcher in the Major Leagues, playing for the Cleveland Indians from 1941-1958. Ted Williams rated Bob as a fantastic pitcher, and after he retired from playing ball, Bob had a successful coaching career. In the off-season, we imagine he spent a lot of time in his namesake restaurant, entertaining the regulars with tales of his time on the mound. Bob Lemon died in Long Beach in 2000.

Towne Theater, 1946, Box Office Magazine. Now playing: The Big Sleep

The Towne Theater opened in September 1946, a 1308-seat venue owned by the Cabart Theatres Corporation and designed in the modern style by local architect Hugh Gibbs, whose firm survives.

The Towne was distinguished by its front-of-the-house soda fountain, walled on three sides with glass, and providing views of its social scene to passing automobiles, and to arriving patrons, whose waits were shortened by the novel two-cashier ticket booth.

Towne Theater lobby, 1946, Box Office Magazine.

In keeping with the modern philosophy, the design of the screen was treated minimally, with no fussy decorative elements, just a simple curtain skimming a carpeted rise.

The Towne Theater served its suburban clientele well for three decades, and was demolished in the 1970s.

photo: George Mann

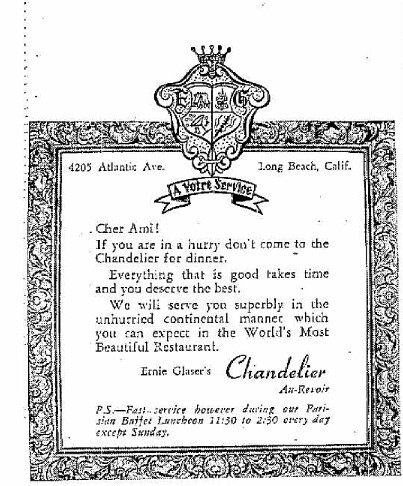

Two blocks south, and our next stop is Ernie Glaser’s Chandelier, which was billed as The World’s Most Beautiful Restaurant and featured “food on the flaming sword” — torched tableside by waiters in evening dress bearing custom-forged weapons equipped with special hilt-cups filled with volatile liquors.

You’d be forgiven for thinking “how cute, they put a restaurant in one of those 1930s storybook cottages” — but, in fact, The Chandelier was purpose-built for Ernie Glaser in 1955 by architects Francis Osmond Merchant and J. Richard Shelley, at a reported cost of more than $100,000. (Merchant and Shelley would soon build the 12-story modernist co-op Royal Palms Apartments, near the shore in Long Beach.)

Now what was so darned beautiful about The Chandelier? Certainly the three namesake light fixtures, each with a dazzling Old World back story, glittered attractively. And who doesn’t dig fairy tale architecture? Or a French buffet luncheon? Or Parisian torch singers strolling among the diners? Mais oui!

But we suspect the aesthetic highlight of any meal might well have been interacting with the two lovely hostesses decked out in their microscopic French maid costumes. Meet blonde Vicky Dyer, who with brunette Kathy Burns was on hand to escort diners to their tables and ensure that no guest felt unappreciated as the theatrical experience that was an Ernie Glaser meal began.

German-born Ernie Glaser was a popular host, always dreaming up something spectacular to leave his guests bedazzled. Ernie was good with a nickname, too: who wouldn’t want to dine at a restaurant run by the “caterer to kings”? (Italy, Greece and Albania if you’re keeping count, and if you’re thinking Italy doesn’t have a king, think again.)

And energetic: at the time he was overseeing the building of The Chandelier, he was managing the Cellar Club at Long Beach’s landmark Wilton Hotel, where he’d opened Conrad Hilton’s Sky Room lounge in 1938, and working for the civil defense program as a survival training chief.

Glaser also had a Swiss-Bavarian restaurant on Ocean Boulevard, Heidi’s (named for his wife, its hostess), featuring one wall decorated as a miniature Alpine village with wee chalets and real waterfalls, and membership cards proclaiming regular customers citizens of the imaginary nation of Swissany.

After a few years, Ernie and Heidi moved out to Palm Springs with their teenaged daughters. In 1959, Heidi was driving with her daughters near Murrieta Hot Springs when her car hit a boulder in the road and overturned. Heidi was killed and her children badly hurt.

In later years, Ernie remarried and had two more children, managed a luxury restaurant chain in Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands and hotels in St. Louis, returned to the Wilton Hotel as catering manager, was GM of the El Caballero Country Club in Tarzana, and launched a gourmet popcorn company offering bleu cheese, bacon, enchilada and chili-flavored varieties.

The Chandelier continued on under owners who lacked Ernie’s flair. It was Puccini’s for some years, then the Chalet, then the Chandelier again. Don’t go looking for this Norman charmer, formerly found at 4205 Atlantic Boulevard; today the site holds a mini mall anchored by a Trader Joe’s market.

Photo: George Mann

We’ve struggled to identify the location of this charming little drive-in, all the cuter for its placement against a threatening sky. The Clock in Bellflower was famously a stop along the 1950s teenaged automotive cruising circuit, but seldom if ever photographed, so we can’t say with certainty if this is that most famous Clock.

A foreclosure auction listing from April 1961 lists no fewer than 14 Clock drive-ins scattered across the Southern Californian landscape”¦ and on the list was one Clock located smack dab along George Mann’s short photographic route down Atlantic Boulevard.

Since we know George would have passed the location, and in the absence of evidence to the contrary*, we’re provisionally placing this restaurant at the intersection of Atlantic and Carson. Signs on the front instruct visitors that the few parking spots are reserved for car service customers, which on this gloomy day consists entirely of the couple in the white and green Chevy Bel-Air or Impala (1959 model). Here’s hoping they enjoy their meal and have a safe trip home.

*evidence has emerged! Thanks to the good folks on the “born and raised in long beach”group who did the digging to identify the Clock Drive-In pictured as one located three miles to the north in Long Beach at Atlantic and Artesia.

Photo: George Mann

Our final stop on this time travel trip to Bixby Knolls is to a restaurant that we could have visited quite recently. Sadly, in May 2010, after 59 years of service, Arnold’s Town House Family Restaurant lost its lease and was shuttered.

A cafeteria until the bitter end, Arnold’s was the urban flipside to restaurateur Miles Arnold’s popular Arnold’s Farm House in Buena Park, home of the giant neon windmill (demolished for redevelopment). In later years, Arnold’s was owned and operated by Ray Johnson, then by his son Mike.

We can live vicariously through the Yelp reviews, and learn that unlike some old school joints that trade on their reputations, Arnold’s was making folks (mostly older ones) happy with unpretentious comfort food and gracious service until the doors the locked for the very last time. Also in the Yelp comments, the troubling suggestion that Arnold’s was another victim of the ongoing mortgage crisis.

This sad note concludes our guided tour of Bixby Knolls as it was. We’ve traveled half a mile and fifty years, only to end up right back here in 2012, in a sometimes too-modern world where restaurants are “concepts” launched by investment consortiums, where signage is approved by committee and manufactured without artistry, but where the people are still hungry for well-prepared food, attractive surroundings, and for a place they can feel welcome. Here’s to the memory of great restaurants lost, and to the fantastic joints of today that our grandchildren will feel nostalgic for in decades to come.

Stay tuned to On Bunker Hill for our next trip in the footsteps of photographer George Mann, when we’ll be featuring the glamourous dining options along Restaurant Row, Hollywood, and a few surprises.