"If they are ignored, [Alice] Callaghan worries, the dangers of handing the streets over to private security forces will only grow. ‘Until they begin interfering with the rights of middle-class people,’ she says, ‘you won’t have anybody crying about it. But by then, it will be too late.’" ”“ Ben Ehrenreich, L.A. Weekly, May 24, 2001

Downtown Los Angeles is my beat.

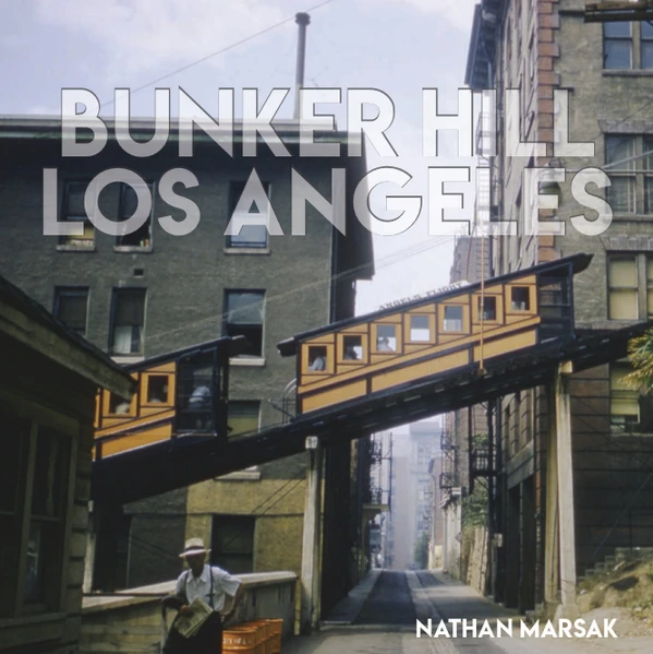

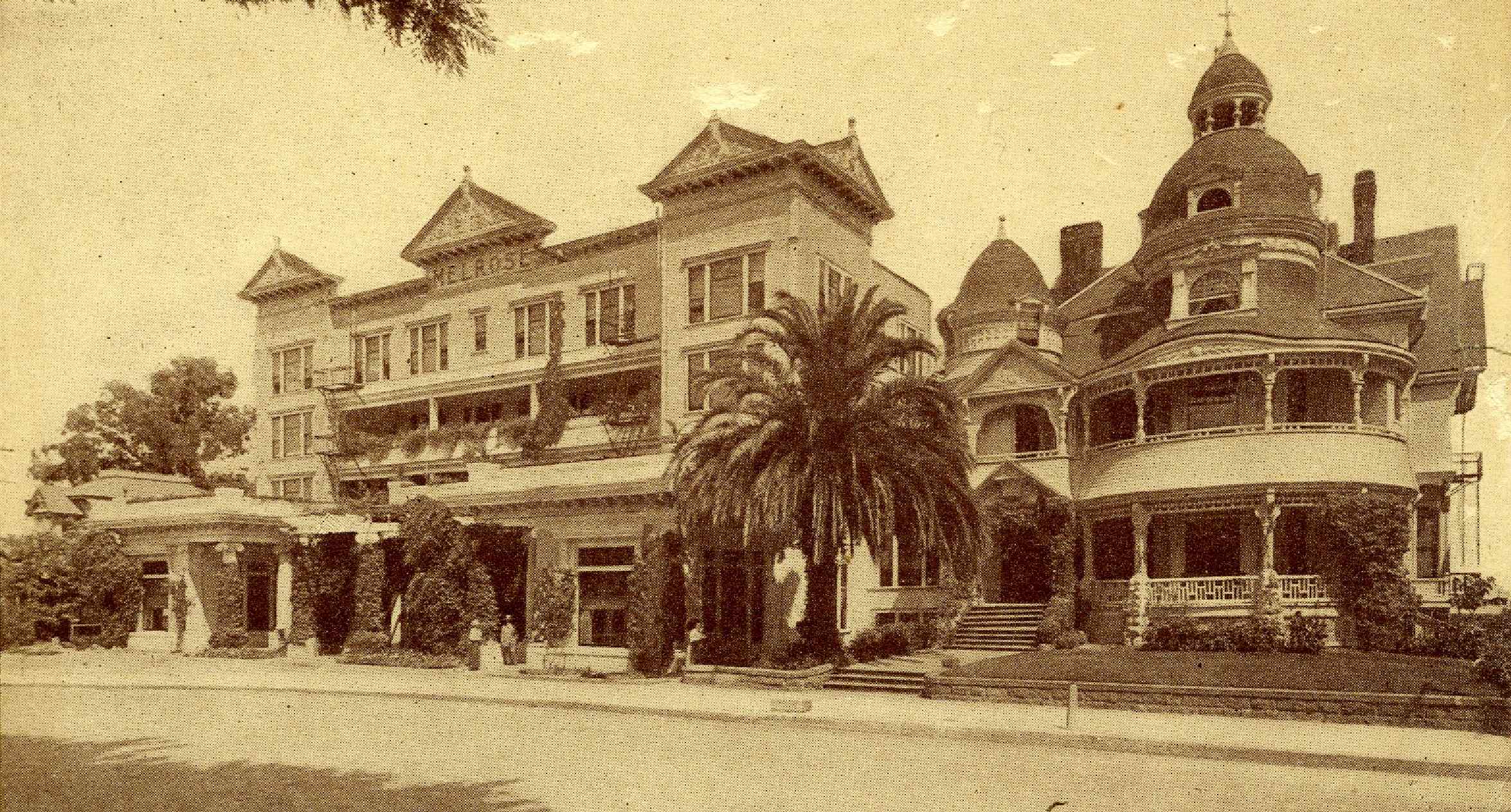

The fine old business and entertainment district, left nearly untouched as the city threw out her arms in postwar sprawl, is presently growing a new cycle of memories with the adaptive reuse of long-empty office buildings into high-priced loft apartments.

But for all the considerable #DTLA hype, the really interesting stuff is found layers beneath the trendy bars and cafes, the developer-subsidized gallery scene and the mainly young, white, upwardly-mobile residents exploring the pleasures and challenges of life in a transitional urban community.

When you know where to look, downtown is pocked with lore, loss and loveliness: unsolved murders, gorgeous architecture, hidden bootleg and subway tunnels, dilapidated movie palaces turned megachurches, amethyst glass sidewalks illuminating sealed basements–even the actual shabby hotel lobbies where a young Raymond Chandler observed the characters who’d inhabit his noir narratives.

For many years, the main threats facing these evocative spaces were entropy, earthquake and disinterest.

Then came gentrification. And Occupy. And chalk.

The developers arrived in 1999, palms open for handouts from a Redevelopment Agency that had long since redefined the blight it was formed to combat. Rough streets made hard pillows for thousands, while up above, market-rate renters coddled doggies behind steel doors. Big chunks of Main Street, long the eastern Maginot Line behind which the needy were corralled, were snapped up by a favored developer, and the rescue missions and social service agencies were shooed further east, towards the concrete barrier of the L.A. River.

The Occupy LA encampment sprung up around our iconic City Hall on October 1, 2011, was initially welcomed by Mayor and City Council, and forcefully evicted by LAPD on November 30. The threatened bill to taxpayers, mainly for police overtime, hovers around $4 Million. There has been no suggestion that the public officials who asked protesters to stay might be held liable for any of these costs.

Pushed out of the core of downtown, not wanting to fold up their (figurative if not always literal) tents, some Occupiers found themselves at the "other" local Occupation, the media-invisible Occupy Skid Row encampment at 4th and Towne Streets.

Occupy Skid Row was, until its summer 2012 LAPD / County Health Department eviction, the longest surviving American Occupy camp. Unlike occupations in urban centers, this one grew up in a neighborhood that was already home to thousands of poor, addicted, ill and needy citizens. In a city that has failed over decades to deal humanely and effectively with the homeless, a few more tents bedecked with idealistic slogans made no difference… at least at first.

But as the City Hall contingent got familiar with the rhythms of life on Skid Row, and spent more time with socially-conscious homeless citizens and activists, they got an education in the unique social justice challenges facing the poor and homeless when they sought to cross back over Main Street into gentrified Downtown.

You see, gentrification doesn’t just happen. It has to be helped along. There are a number of effective tools at the disposal of developers seeking to make their buildings more appealing to renters and businesses. But not just any tenants: they need a very specialized group of early adopters who, when properly primed, will serve as an unpaid street team, marketing the value of the community as they revel in their status as "urban pioneers." History shows that soon after bohemians populate a depressed urban neighborhood, wealthy people with bohemian tastes will follow. Then it’s bye-bye bohemians. It was ever thus.

Some gentrification tools are transformative: lease large ground-floor spaces to gallerists willing to take a chance in a bad neighborhood in exchange for five years of negligible rent; don’t charge pet deposits; subsidize an Art Walk; open restaurants that keep extended hours to create a community space.

Other tools are restrictive. It seems such a small step from having security guards inside locked lobbies and garages to instructing maintenance crews to hose down the sidewalks at 4am to dispatching teams of security guards to enforce the social order through intimidation and walkie-talkies that connect directly to the real police.

But that small step is the distance from private property to public space, and in the New Downtown, that’s a distinction that’s blurred and frequently abused by "The Shirts," the color-coded security details employed by varied BID (Business Improvement District) entities that have carved up Downtown into discrete zones.

The city doesn’t clean the streets frequently enough? Don’t pester your Councilman; the BID will do it. Insufficient police presence to deter drug dealing and prostitution? Nothing a crew of beefy guys on bikes and Segways can’t handle. And why should anyone complain? BIDs are financed through commercial property tax diversion, not out of residents’ pockets, and everyone benefits from cleaner, safer streets.

The problem is that when a business lobby takes over civic services, they absorb civic power, with none of the accountability. Residents are encouraged to simply call the BID when they see something troubling on the streets, and a crew will show up and "deal with" the problem. (Conveniently, crimes reported to BID security are not recorded in LAPD crime statistics, making BID-protected neighborhoods appear safer than they really are.)

And as landlords make decisions about which sort of people are allowed to stroll or linger, unmolested, on public streets, a chilling effect spreads. Tired of being hassled, the poor and the undocumented and the weird stay away. Demographics normalize. Rents go up. Yoga studios move in. It’s an urban redevelopment success story– at least it looks that way on the surface.

Seeking a fresh focus for a movement that had grown bored with the dry crimes of banks, Occupy LA activists decided to drill beneath Downtown’s surface. What they found was the woman behind the curtain: Carol Schatz, President and CEO of the Central City Association and of the Downtown Center BID. Ms. Schatz and the powerful organizations she controls are well-known in the business community, but obscure to the general public.

In late May 2012, a decision was made by Occupy LA, LA CAN, Occupy The Hood, Occupy Skid Row, Hippie Kitchen, Los Angeles Catholic Worker and other community groups and individuals to establish a protest camp on the public sidewalk outside CCA’s headquarters at 626 Wilshire. The intent was to draw attention to ways in which the CCA’s Downtown 2020: Roadmap to L.A.’s Urban Future position paper (PDF link) seeks to criminalize homelessness and poverty in order to create a more business-friendly environment.

The protest was peaceful, if occasionally disruptive to those doing business at 626 Wilshire. Tents were set up on the sidewalk in the evening, and removed in the morning as workers arrived. Occasional daytime protests were scheduled to coincide with large meetings of CCA member organizations. Discussion groups gathered, drums were pounded, security guards razzed and preached to, dissenting messages scrawled in chalk on the sidewalk. The peculiar orientation of the building, one very short block from where Wilshire dead ends, meant that during the night camps there was minimal foot traffic and no impediment to local business.

The plan was to camp out for a week–and considering that the campers got few visitors and received no media attention, the protesters would almost certainly have moved on, had they not been subject to unwarranted police harassment.

I dropped by 626 Wilshire a few nights after the camp was formed. Perhaps a dozen people were gathered on the sidewalk. They were a varied group: men, women, multi-racial. A young man and an older woman approached me separately, and each made pleasant conversation about social justice issues. They seemed happy to have someone new to talk with. Across the street, I saw an LAPD patrol car parked with two officers in it. Around the corner, a second black and white lurked. It seemed an excessive response for a peaceful gathering on a public sidewalk.

Within days, word filtered out through Occupy LA’s social media accounts that protesters were being arrested for chalking.

Still, there was no press attention. No criminal charges were filed. The arrests continued. People felt intimidated and angry. The "siege" was indefinitely extended.

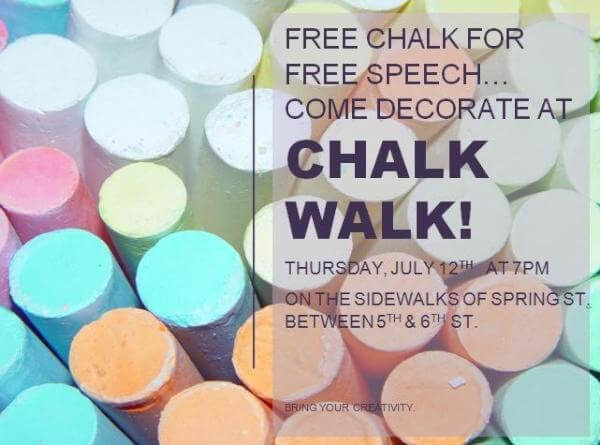

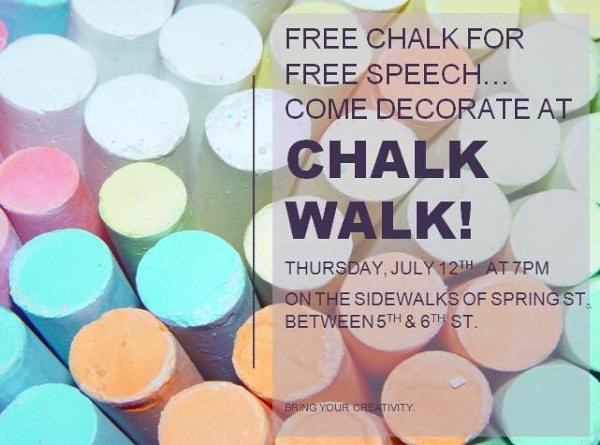

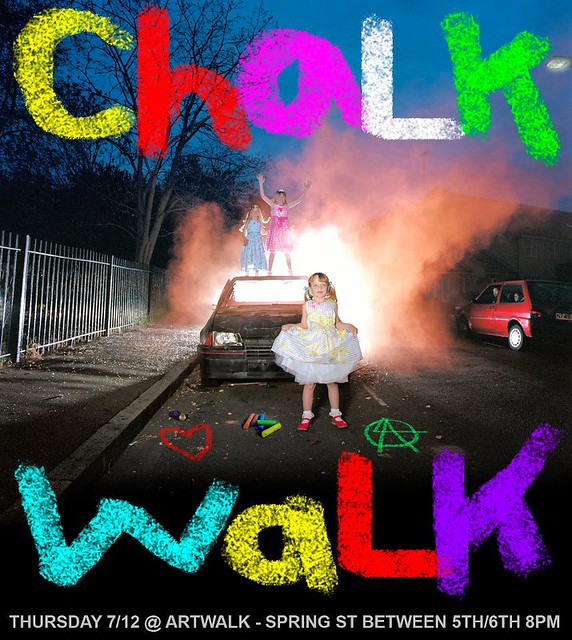

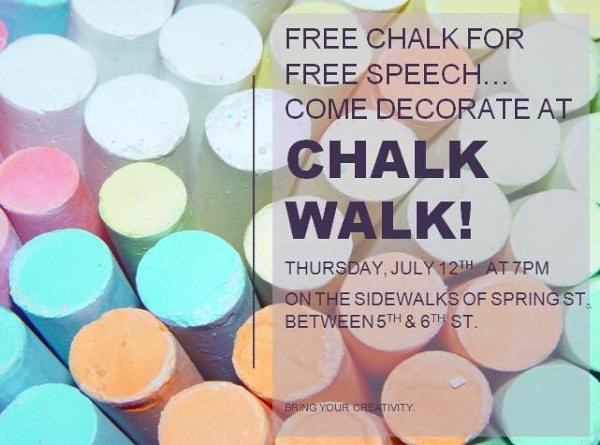

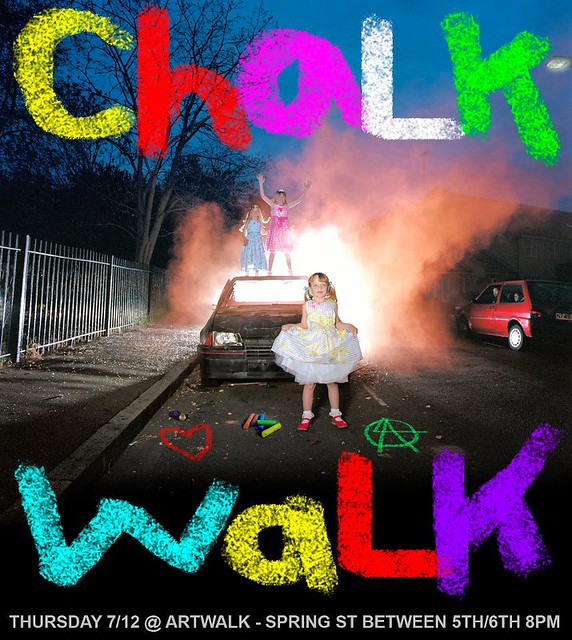

Several individuals organized a Chalk Walk on July 12, during the monthly Downtown Art Walk, in order to bring the story of the arrests to a wider audience. The slogan was FREE CHALK FOR FREE SPEECH. Most participants were members of Occupy LA, although it was not an official OLA event.

That Thursday around 7pm, about two dozen people gathered on Spring Street between Fifth and Sixth Streets handed out sticks of washable sidewalk chalk wrapped in information about the CCA protests and chalking arrests to Art Walk attendees.

By 7:15pm, the protesters were surrounded by approximately 40 LAPD officers, and the first chalking arrest was made. Many people stopped and chalked. As dusk fell, the police presence grew, and more people were arrested. At 9pm, police donned riot helmets, and many of the protesters left for a planned fundraiser. At 9:15pm, there were so many police massed on Fifth Street that traffic was impeded and a curious crowd formed.

Around 9:30pm, the rough arrest of a petite woman incensed the gathering crowd, and they poured into the intersection. The police responded with riot tactics, breaking up the crowd by running three skirmish lines: north, south and west. At 10pm, the first less-lethal projectiles were fired. As the police moved south into the commercial heart of the Historic Core, they begin closing galleries, restaurants and residential buildings and not permitting anyone to enter or exit.

By the night’s end, at least three Art Walk attendees would suffer beanbag wounds to their torsos, and one to his face, 17 people would be arrested, two police officers would suffer minor injuries, thousands of people would be terrorized, and numerous artists, vendors, galleries, restaurants, bars and food trucks would suffer financial harm.

A troubling toll, and yet it’s hard to see the event as a failure, since the goal of raising consciousness was achieved. On Wednesday night, the CCA was a mystery. By Friday morning, it was the centerpiece of a dozen newspaper articles, some nationally syndicated. Complex issues like the dark side of gentrification, private security in public spaces, and the criminalization of poverty got a rare airing. And suddenly, Occupy LA was as relevant as it had ever been.

As the August 9 Art Walk approached, tensions were high over what role chalk protests and Occupy might play. My husband Richard Schave and I, as the people who had run and put the Art Walk into a non-profit in 2009, only to be forced out due to sabotage by the local BID director, were approached by a member of Occupy LA who was concerned about the potential for further violence. We reached out to the Mayor’s Office and to the Art Walk Task Force seeking dialog, and helped organize a Town Hall meeting, where activists, artists, vendors, business people and residents shared their concerns, frustrations and hopes for peace.

Days passed. Some worried because The Fresh Juice Party, chalk muralists affiliated with Occupy Oakland, planned to attend Chalk Walk 2. Police spokesmen said anyone chalking would be jailed–and indeed several muralists were detained and one arrested. But as darkness fell, the police pulled away from Pershing Square, where the protesters were gathered around a large cartoon mural of a lion and a duck with a word bubble message "I ♥ The 1st Amendment / Chalkupy!"

A young woman stood on the mural, hula hooping. Folksinger Michelle Shocked, who has been using the name Michelle Chocked for anti-BID art actions, played a set. A couple of Fresh Juice Partiers donned animal costumes, and brought their mural to life with a slapstick chase. People crowded around the wide concrete wall, inscribed with a quote from Nation editor Carey McWilliams about the lively community of oddballs that inhabited Pershing Square in the 1930s, and chalked words and pictures in a riot of color and expression.

It was the best party Pershing Square had seen in decades. And the next morning, the press praised all concerned for restraining themselves on a battleground that wasn’t really a battleground, just a square block in the heart of the city, where after much tension and blessed release, we saw what was possible when fun overruled fear, and art trumped enforcement.

And on an urban stage where the actors can appear to be placed in the pose of scrappy street fighters vs. armored warriors, with reporters in helicopters screaming "Occupy Riot at Art Walk!" to footage showing no such thing, the fact is that Occupy can still turn, fluid as an eel, and transform the scene, the context and the conversation surrounding a local injustice. It’s more than a little uncanny, and thrilling to watch. And anyone who is counting this magickal child out as she approaches her first birthday hasn’t been paying attention.

Downtown is still a mess, albeit a beautiful one. And the war’s not over, not by a long chalk. But there’s hope on the wind, and humor, and dialogue. And no telling how these creative protests will change us next.

*

This essay was originally published in Occupy! #5.

Occupy! is an OWS-inspired gazette, published by n+1.

http://nplusonemag.com/occupy

*

Sources

Chalk Walk timeline in video and photographs – http://ccacdtla.wordpress.com/

626 Wilshire protest website – http://626wilshire.wikispaces.com/

Michelle Chocked video for "Graffiti Limbo" – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wi-K2cDDeEU

Fresh Juice Party performance at Chalk Walk 2 – http://www.ustream.tv/recorded/24595035/highlight/284179

Chalk Walk 2 video – http://peteyk.com/?p=538

"Downtown 2020: Roadmap to L.A.’s Urban Future" – http://ccala.org/downloads/DT2020legislativeprioritiesJan2012.pdf