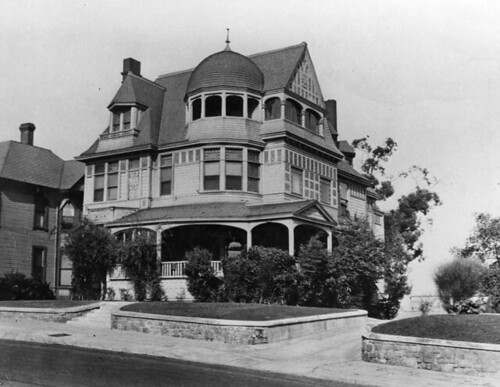

As Bunker Hill developed from a fashionable Victorian neighborhood to an area of somewhat slummy dwellings, the grand mansions of the earlier era adapted with the times. In most cases, the large homes were converted into multi resident housing, sometimes a mere decade or two after construction. However, there are rare cases of Bunker Hill homes being inhabited by one family from the beginning to the bitter end, as was the case with the Larronde home at 237 North Hope Street.

At one time, the name Larronde was a fairly well known one in the City of Angels. Pierre Larronde was a native Frenchman who landed in San Francisco in 1847 and made a killing in the gold mines. When he relocated to Los Angeles in 1851, he amassed a further fortune by successfully raising sheep on one of the Ranchos. Always the astute businessman, Larronde cashed out his sheep empire in the late 1880s and focused his energies on real estate. His holdings included prime land at the corner of First and Spring, and a parcel on North Hope Street near Temple where he built the family home.

Pierre Larronde had a great deal in common with a fellow Los Angeles pioneer named Jean Etchemendy. Both men hailed from a south western region in France called the Basses-Pyrenees, both briefly lived in South America before cashing in early on the Gold Rush, and both successfully settled in Los Angles as sheep ranchers. Last but not least, both men married a gal named Juana Egurrola. Juana was born in Marquina, Spain but moved to California with her family at a very young age. She married Etchemendy in 1865 and gave birth to daughters Mariana, Madeleine and Carolina. Jean Etchemendy died in 1872 and Juana mourned for a couple of years before hooking up with the other French sheep-man in town. Juana”™s 1874 union with Pierre Larronde produced three children, Pedro Domingo, John and Antoinette.

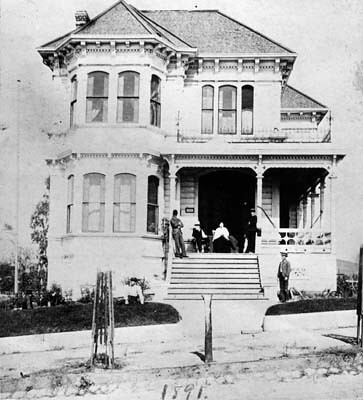

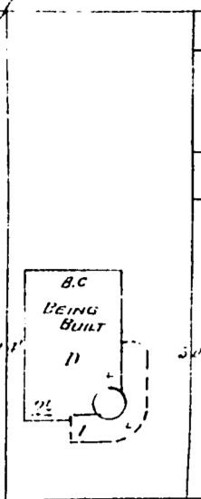

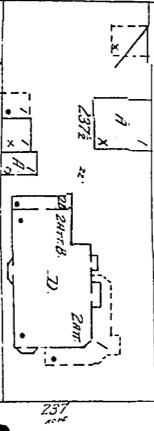

The Sanborn Fire Insurance maps show the house on Hope Street as being under construction in 1888. The Larronde Bunch moved in shortly thereafter and held gatherings on a regular basis that made the society pages. Unlike many residences of Bunker Hill, the Larronde home suffered no scandals or controversies. Pierre the pioneer died in 1896, around the age of 70, and Juana resided on Hope Street until her death in 1920 at the ripe old age of 84.

Of the six Larronde/Etchemendy children, only two ventured off of Hope Street. Pedro Domingo would become a principal in the Franco American Baking Company and Antoinette married James J. Watson and had three children. John served as the head of the Fire Commission for a number of years and lived at 237 N. Hope Street until his death in 1954. The three Etchemendy girls also lived in the mansion for decades. Madeleine died shortly after her stepbrother in 1954, and Caroline and Mariana would live on for another decade.

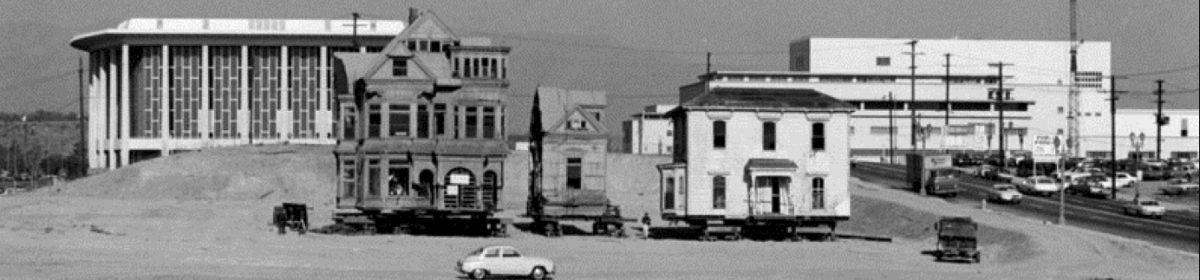

For nearly eighty years, one family resided in the house at 237 North Hope Street. By the

end of the 1960s, all traces of the Larronde/Etchemendy clan were erased from Bunker Hill.