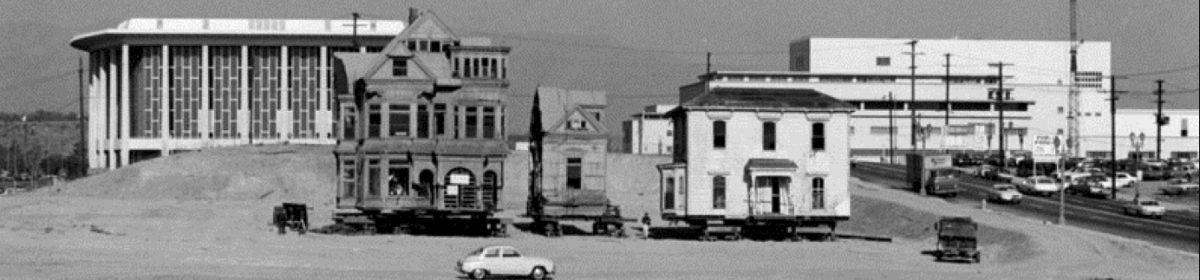

When the Castle and Salt Box were physically moved from Bunker Hill to Heritage Square in Highland Park, it was probably a sight most residents had never seen. However, this was not the first time a home on the Hill was relocated. Almira Hershey outdid them all in the early 1900s by not only moving her Bunker Hill home, but by also splitting it in half and transforming it into a massive and majestic apartment building.

Almira Hershey, better known as Mira, is a name that was once prominent in Los Angeles, but is now pretty much (and unfortunately) forgotten. She was a relative of Milton S. Hershey, founder of the Pennsylvania chocolate empire, and the daughter of Benjamin Hershey who amassed a fortune in the lumber and banking industries. Mira inherited a substantial sum when her father died and she relocated from Muscatine, Iowa to Los Angeles in the 1890s.

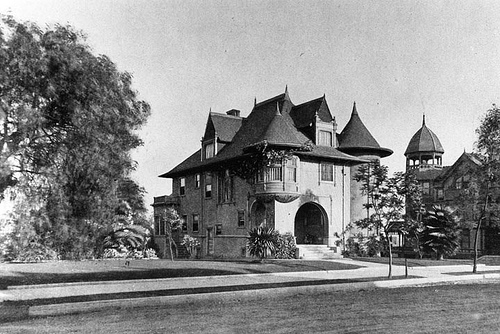

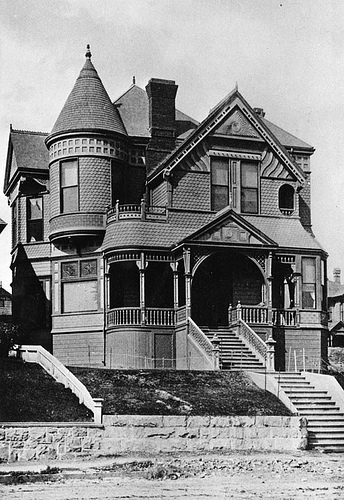

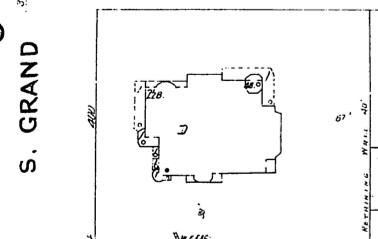

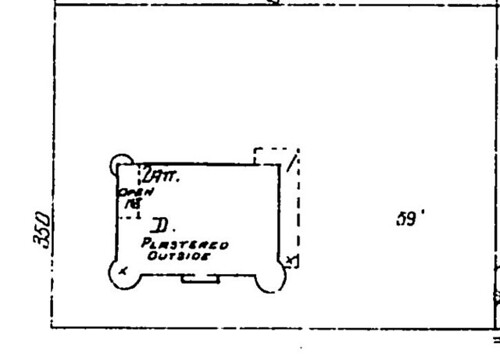

Hershey purchased real estate on Bunker Hill and commenced construction on a number of residences, including her own home at the NE corner of Fourth and Grand Avenue in 1896. The elegant structure sat across the street from the Rose Residence, and cost $5,000 to build (around $123,000 in today’s dollars).

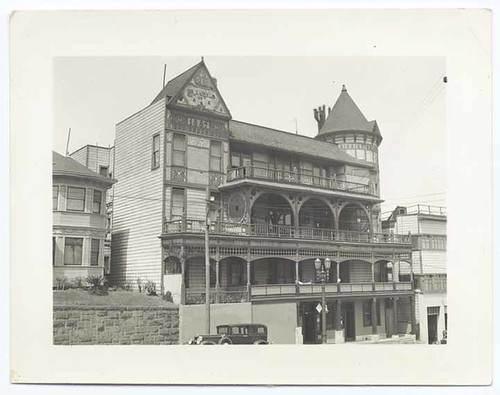

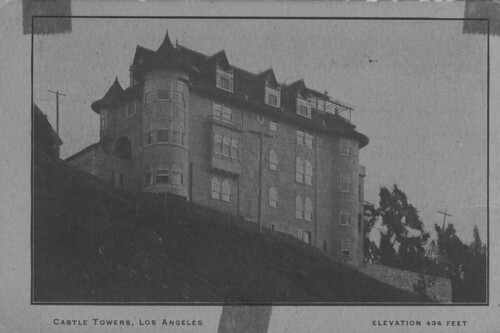

After living at 350 South Grand for ten years, Hershey decided she needed a change. Instead of merely redecorating, she physically had the house moved to 750 W. Fourth Street and commissioned architects C.F. Skilling and Otto H. Neher to split the residence in half and turn it into an apartment building. The renovations on the new building were completed in December of 1907 and the finished product included one and three bedroom suites complete with patented wall beds, artistic wall decorations, and interior wood finishings. Because of the structure’s resemblance to a European castle, Hershey’s new apartment building was christened the Castle Towers.

As for the prime lot on the corner of Fourth and Grand, Hershey had plans to build a hotel on the location of her former residence, and again hired Skilling & Neher. The concrete foundation had been laid by March of 1908, but plans were halted a couple of weeks later when the architects filed a lawsuit against Hershey for nonpayment of fees. The hotel was never completed, and the concrete foundation was turned into a parking lot that would remain until the neighborhood was completely redeveloped in the 1960s.

Mira Hershey did go on build her hotel called the Hershey Arms on Wilshire Boulevard. She also fell in love with the famed (and former) Hollywood Hotel, which she purchased and lived in until her death in 1930. She was so enamored with the building at the corner of Hollywood and Highland that she commissioned a replica, the Naples Hotel, be constructed in a Long Beach neighborhood.

Mira Hershey was always quick to share her wealth, but kept her philanthropic activities private after the Los Angeles Times attacked her for donating money for a hospital to be built in her hometown of Muscatine, Iowa instead of her current home city. One of Hershey’s most significant donations came after she died and her will revealed that she left $300,000 to UCLA for the construction of the school’s first on-campus dormitory. Countless students would call Hershey Hall home for decades.

As for the former residence-turned-apartment building, the Castle Towers and its residents lived a peaceful existence and until the mid-1950s when the Community Redevelopment Agency came a callin’.

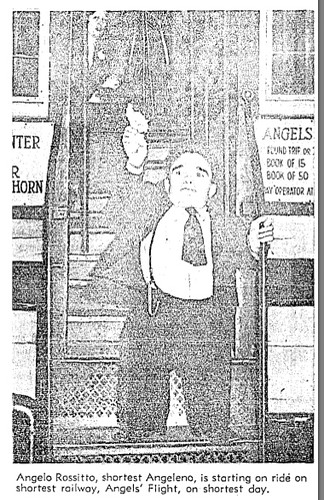

Photo courtesy of the Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection. Postcard from the personal collection of Christina Rice.